Anatomy of a Bitcoin phish

You’ve probably heard of Bitcoin, the digital currency that has no central control.

You’ve probably heard of Bitcoin, the digital currency that has no central control.

Bitcoin relies on complex cryptographic calculations (or, more accurately, on deliberately time-consuming ones) and a globally, public database known as the blockchain that allows its digital “coins” to be owned by just one person at a time.

Bitcoin isn’t strictly anonymous, because the blockchain contains a record of how the currency’s coins have moved around over time.

But with no regulatory requirement for coin owners to register or to identify themselves, there is no official or reliable way to track coins to their owners.

So, for users who are cautious about their privacy, Bitcoins do work like cash.

And Bitcoins can be spent internationally over the internet without exchange rate calculations, exchange control paperwork, processing fees and other charges, so they are remarkably straightforward and egalitaran, too.

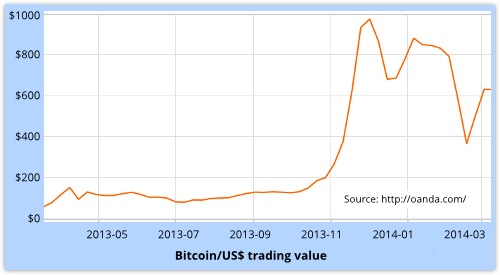

Better still, in the last year or so, Bitcoin has been an currency investment you could keep under your mattress at home yet watch its value appreciate:

Neverthless, the Bitcoin ecosystem has had its fair share of negative publicity over the past few months, for a number of rather turbulent reasons:

- Bitcoin is one of the ways you can pay the extortion money to get your data back if your computer gets scrambled by the CryptoLocker ransomware. Good luck getting any money back, even if the blackmailers get caught.

- A number of boutique Bitcoin exchanges (where you can trade regular money into and out of Bitcoins) have quickly attracted millions of dollars of digital data, and then vanished in puffs of cybersmoke. Good luck getting any money back.

- The biggest Bitcoin exchange of all, Mt Gox, imploded into bankruptcy recently, with more than $500,000,000 worth of Bitcoins missing. Good luck getting any money back.

In other words, at the small, medium and large ends of the Bitcoin world, operational failures and abuses have brought the Bitcoin ecosystem under both scrutiny and suspicion.

Phishing Bitcoin users

Unsurprising, then, to see the phishers getting in on the act.

Phishing, of course, is a cybercrime that involves tricking you into giving up personal information – most notably, usernames and passwords for online services – through visual deception.

Typically, phishing is conducted via email.

The crooks send out a messages, sometimes to a targeted list, at other times spammed as widely as possible, to lure you to a website.

They might urge, frighten, cajole or bribe you into action.

Examples include: presenting you with a free offer; warning you that your bank account has been hijacked; asking you to re-confirm your account; or giving you the happy news that you just got a tax refund.

The idea is to get you to click on a link, go to a website associated with a brand you know (and presumably trust), and feel comfortable there.

Then the phishers present you with a login screen that is believable enough that you put in your username, password, and possibly other details…

…before realising that you just submitted a web form full of PII (Personally Identifiable Information) to bunch of imposters!

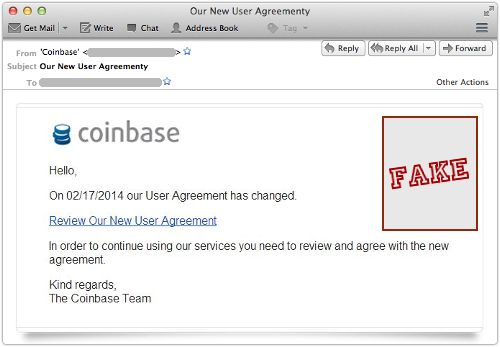

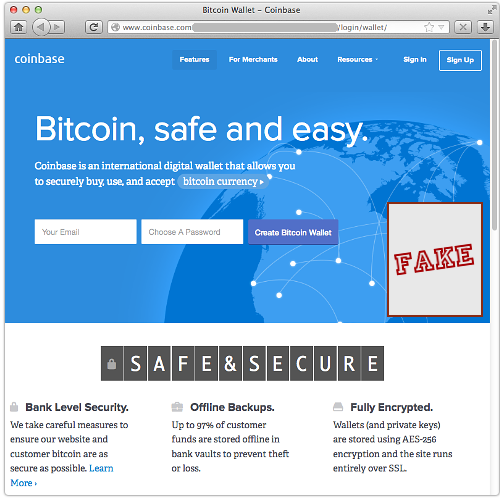

Just like this:

Coinbase is a boutique Bitcoin exchange, based in downtown San Francisco, that despite its small size claims to service about 1,000,000 accounts.

That’s more than enough active users for scammers to reach a reasonable number of potential victims even with a randomly-blasted-out, totally untargeted spam campaign.

In this case, the phishers have let themselves down a bit with typos and bad grammar (the word “agreement” spelled as “agreementy”, for example), but the email passes muster at first glance.

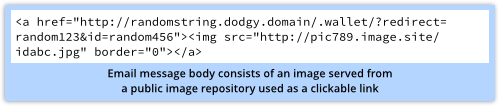

The message body, as it happens, consists a single line of HTML:

The “text” you see in the email screenshot above is actually fetched as a pre-rendered remote image, which has several benefits for the phishers:

- The content of the message is easy for humans to read and understand, but hard for a spam filter to convert into words or concepts.

- The look and feel of the message can be changed between the time it is sent and the time you open it.

- The use of unique text in the URL linking to the images will signal to the crooks that you opened the email, even if you don’t go on and click anything.

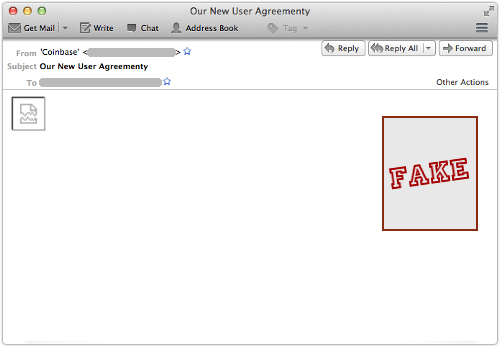

Of course, using a remote image can also be an advantage to you, because most email clients can be configured to ignore remote images, or at least to fetch them only at your explicit request.

By default, for example, Thunderbird shows you no more than this:

→ We recently published a list of tips telling you how to block remote images in seven of the major email services. If you aren’t blocking remote images already, you might want to considering doing so.

If you click through, you end up at a surprisingly realistic facsimile of the real Coinbase site:

Sadly, it’s not hard for crooks to produce a good-looking clone of a legitimate site.

Because websites are transitted to your browser and rendered there, crooks can simply visit a regular website and record the content that comes back – HTML, stylesheets, JavaScript files, images, and so on.

They can use this captured content, usually with only small modifications, to serve up their own facsimile site, complete with pixel-perfect logos and word-perfect corporate messaging.

But there are three important differences between the real site and the fake.

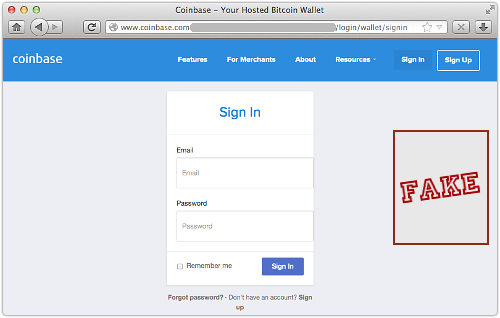

Difference One

The imposter site pops up a “Sign In” window wherever you click, not only if you choose the sign-in option.

Nevertheless, the bogus login screen is once again a realistic-looking fake:

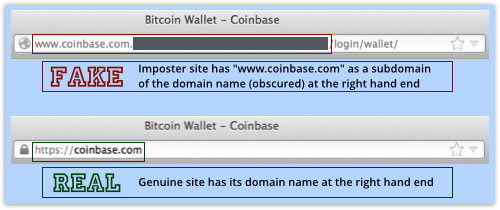

Difference Two

The domain name in the address bar contains www.coinbase.com, but at its left hand end.

That means it is merely a subdomain of a site name (obscured above) that is controlled by the crooks.

You need to check the right hand end of the site name in order to see where you are going.

→ To get the domain name example.com, I’d have to register it, and then no-one else could use it. But once I’d registered it, I could create subdomains underneath it called anything I want, such as your.site.name.example.com.

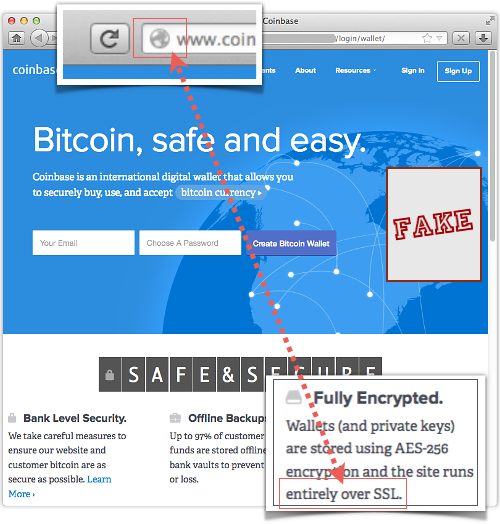

Difference Three

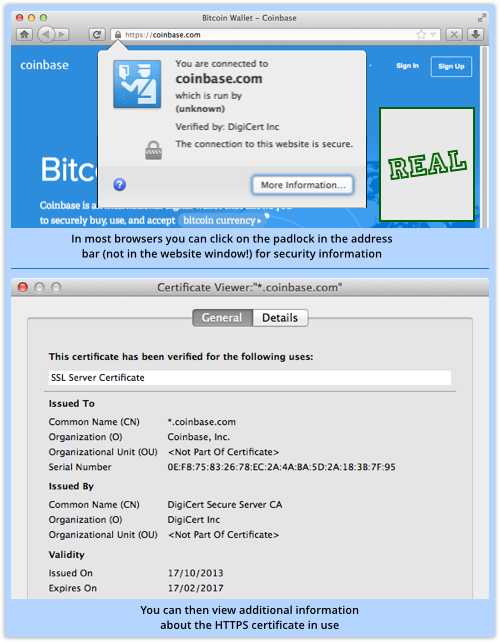

Even though the crooks have carefully copied the claim that the Coinbase site uses SSL (HTTPS) throughout, the clone site is plain old HTTP.

The crooks don’t have Coinbase’s private encryption key, so they cannot easily pretend to be Coinbase’s encrypted website.

So, to avoid the HTTPS certificate warning you would see if they tried to mock up https://coinbase.com/, they have simply included the text coinbase.com into the URL for verisimilitude, and hoped that you won’t notice the lack of HTTPS.

What to do?

Learn to notice when HTTPS is missing – it makes a phish like this really obvious.

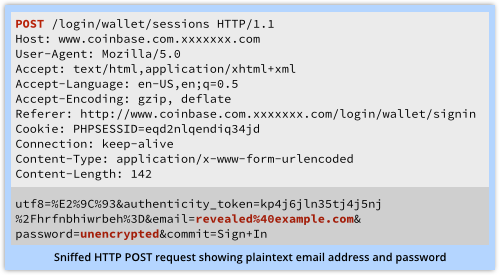

By the way, there’s a secondary risk if you enter your PII onto an unencrypted phishing site.

You don’t just reveal your personal data to the crooks running the imposter site, but also to everyone else on your network at that moment.

That’s because your data travels back unencrypted over the internet, where anyone else on the network between you and the crooks can sniff it, see it, and save it.

So, watch out for that HTTPS padlock – you can click in the address bar to bring up details about the connection and, if it’s encrypted, who claims to be running the encrypted server.

And when you are presented with a login screen, don’t be too quick before you click!.

Image of magnifying glass courtesy of Shutterstock.

Article source: http://feedproxy.google.com/~r/nakedsecurity/~3/cmesM0pmd7s/