Anatomy of a “free” gift – how online surveys can harm your digital health

Over the weekend, we received a short, sweet and simple note.

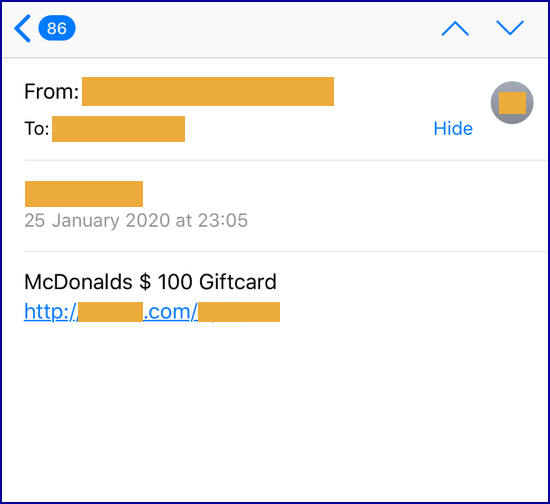

It arrived by email, but the crooks could easily – and for all we know, did – use the same content in an SMS or text message:

We weren’t tempted, not least because of the giveaway HTTP link – which was a fortunate blunder by the sender, because the redirector site they were using immediately transferred us to a more legitimate-looking HTTPS page, complete with security padlock.

(Remember: a web certificate and padlock doesn’t vouch for what’s actually on a web page – it’s called a TLS certificate, short for Transport Layer Security, because it protects the network traffic, even if the data ultimately served up is fake news, malware or a not-so-free gift..)

The other giveaway mistake by the senders of this email is that the amount is in dollars, yet we’re in the UK where a $100 McDonald’s voucher wouldn’t be redeemable.

What if you click?

But what happens if you are inquisitive and you do click through?

To save you the trouble, we decided to take a look on your behalf and report back what happened.

We tried many times from many different IP numbers, using many different permutations of the URL we originally received.

For what it’s worth, the blanked-out text after the / character in the image above seems to be a pseudo-random tracking code, not only because that’s what it looks like but also because removing it takes you to this blunt message:

![]()

When we appended tracking codes to the URL, there were several different themes of landing page we saw, all apparently run by the same company.

(Despite trying many times, including with the tracking code we originally received, the one company whose products never showed up was McDonald’s, the brand used by the sender to lure us in in the first place.)

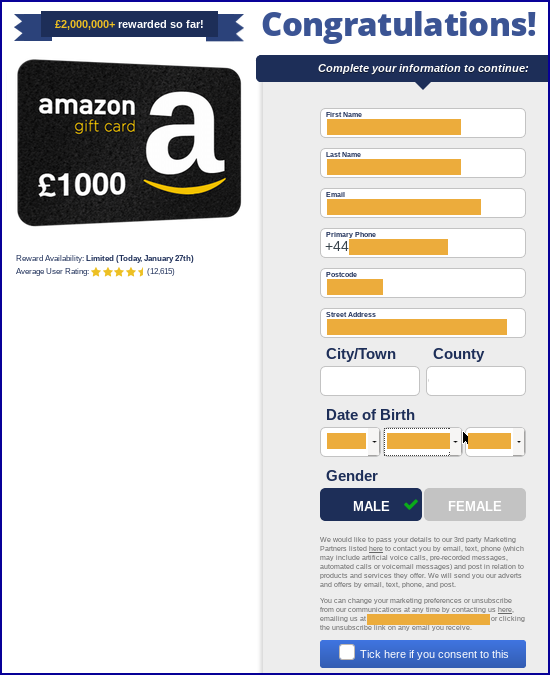

Very commonly, we started off on a page with a “random” spinning wheel offering a range of prizes, where we always lost on the first spin and always won one of the high-value prizes on the “free” spin, like this £1000 Amazon voucher:

At this point, as rigged fake as the prize wheel was, the process had turned into a bit of a game, and it was admittedly tempting just to keep going.

Atter all, someone wins the lottery every week… so perhaps someone gets the gift voucher, too?

To soften you up a bit, the survey starts with three very general questions that don’t feel terribly personal, given that the answers merely divide the participants into broad categories.

You’re asked if you like shopping, your age range, and roughly how much you use Facebook:

But the detailed data collection starts straight after that, with the survey company asking for information including your home address and date of birth:

You’re still not there, of course.

In fact, all you’ve done is qualify to start making the commitments you need to “validate” your claim for the gift voucher (or iPhone 11, or Galaxy 10, or whatever it was when you started out).

The company calls this a “brief survey”, and it’s quick to complete, but you nevertheless end up giving a lot away, and you have to tell the truth, as we’ll see later on:

Now you need to sign up for “qualifying offers”, which is where the survey company starts making its revenue.

You not only have to click through to third-party products chosen by the survey company, but also to sign up for a given number of them.

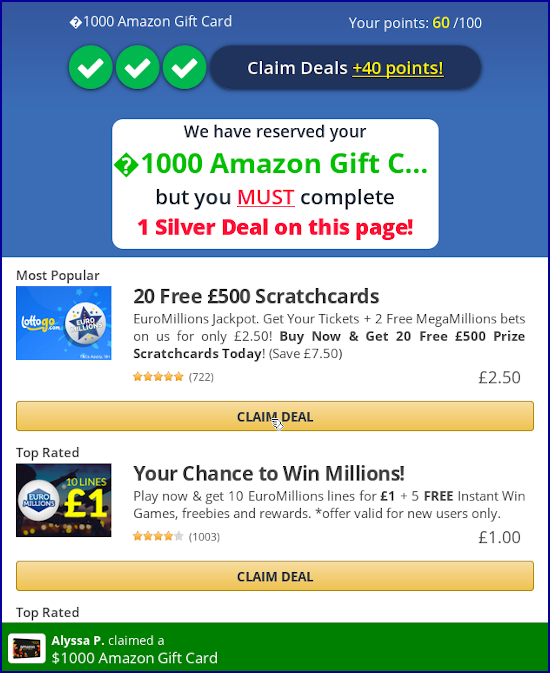

The first offer in our tests was always a choice denoted as a “Silver Deal”, typically for a modest-looking price, as you see here:

At this point, you’re probably wondering how the survey company is going to make a profit if it hands out a £1000 Amazon card in return for a £2.50 scratchcard purchase.

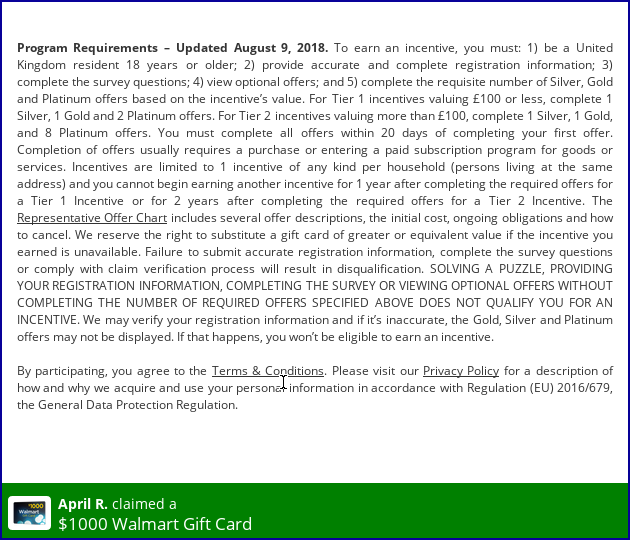

The trap is that the conditions to qualify are a lot more onerous than just making a modest lottery purchase, as you’ll see if you scroll down and read the small print carefully:

These parts jumped out at us:

For […] incentives valuing more than £100, complete 1 Silver, 1 Gold and 8 Platinum offers. You must complete all offers within 20 days of completing your first offer. Completion of offers usually requires a purchase or entering a paid subscription program for goods or services. […] Failure to submit accurate registration information, complete the survey questions or comply with claim verification process will result in disqualification. […] We may verify your registration information and if it’s inaccurate, the Gold, Silver and Platinum offers may not be displayed. If that happens, you won’t be eligible to earn an incentive.

Dotting every i and crossing every t

You’re at the start of a journey that might lead you to a £1000 gift card – we’re assuming that if you dot every i and cross every t in the survey company’s playbook then they will pay out, or else this would be fraudulent – but it seems like a pretty tricky journey.

As far as we could see, there was no way to determine which Gold offers we were actually going to get unless we signed up for one of the Silver offers first.

This not only meant spending money but handing over our details again, including payment card information this time, to yet another company.

The survey company does provide a web page, linked to from the terms and conditions page we showed above, that gives you an idea of the sort of charges you’re likely to face – but without telling you which entries in this so-called Representative Offer Chart are Silver, Gold or Platinum.

There’s also no guarantee that you’ll actually see any offers listed, because the “chart is provided only for guidance and is subject to change without notice.”

We’re guessing that the most expensive offers on the chart are amongst the cheapest you’ll see at the Platinum level, and those range from about £20 to £60 a month.

And you’ll need eight of those offers completed and accepted before you can even think of applying for your gift card.

Remember also that all the personal data you give at any point throughout the whole process has to be consistent.

As far as we can see, if you answered that “brief survey” at the outset a bit too quickly or casually, for example by giving vague or incorrect answers to questions such as your employment or your credit rating, you’ve effectively blown your chances before you even start.

What to do?

In real life, the big financial commitment you’re likely to end up with – remembering that if you decide to call it quits anywhere before your eighth Platinum sign-up then you forfeit your “bonus” – is probably your foremost concern.

But there’s also the issue of having to share your personal data over and over again, lured on by that £1000 promise.

As we said in our guidance for Data Privacy Day:

[Put] your own value on your personal data – figure out how much you’re ready to give away, and what you get in return. If a company or a website asks for more data than it needs, don’t cave in and hand it over unless you want to.For example, it’s reasonable for a car hire company to ask you to offer proof of address before handing you the keys to a $20,000 vehicle. But if a news site or a coffee shop hotspot demands your postcode or your birthday, ask yourself, “Why would they need that, and why would I want to hand it over anyway?”

Know your privacy limits, and stick to them.

And if you have friends or family who are in the habit of filling in surveys because they think they’re mostly harmless, show them this article!

Latest Naked Security podcast

LISTEN NOW

Click-and-drag on the soundwaves below to skip to any point in the podcast.

Article source: http://feedproxy.google.com/~r/nakedsecurity/~3/xTic4Md05yA/