Apple developers – get this update to protect the rest of us!

Apple just pushed out an update to its widely used software development toolkit, Xcode.

New Xcode releases are pretty common immediately after updates to macOS or IOS, typically to provide official support and documentation for new programming features in the latest operating system versions.

The Xcode 11.2 release was a bit different, however, even though it followed closely on the heels of the recent macOS 10.15.1 and iOS 13.2.1 updates.

Xcode 11.2 comes with its own security advisory urging you to get (and then to verify that you have correctly installed) the new version, thanks to a pair of security flaws denoted CVE-2019-8800 and CVE-2019-8806.

These flaws are described in Apple’s typically perfunctory fashion in APPLE-SA-2019-11-01-1 (SA stands for security advisory):

Processsing a maliciously crafted file may lead to arbitrary code execution.

In other words, it sounds as though the supposedly innocent task of just compiling, or building, a software project – something that’s supposed to be ‘mostly harmless’ – could inject malware onto your system.

That might sound like an unspectacular sort of vulnerabiity, given that the first thing you usually do after building a new source code release is to test it, which means running the application you just created, warts and all.

So, crooks who wanted to invade your network via your build system could just add malicious code into the source itself, ready to be compiled directly into the output of the build process.

Then the crooks would just wait for you to run the Trojanised app after you’d built it, which you are almost certainly going to do, otherwise you wouldn’t have bothered to build it in the first place.

Why infect the build system?

However, there’s still a serious issue here, namely that in many companies that build their own software, the build system itself is assumed to be correct and inviolable – it’s carefully and purposefully configured so that the software it creates is never actually executed there.

Simply put, you usually keep the process of creating a new program from source code separate from testing and approving it for deployment.

That way, if there is a dangerous bug in the newly-built app – whether accidentally or deliberately introduced – then you have a fighting chance of finding it during your test process, rather than putting the build system or your live network at risk.

Test systems are generally rebuilt afresh each time they’re used, for example using virtualisation and configuration management software, so that each test stands alone and can’t be affected for better or worse by what happened last time.

For example, if an app requires a specific DLL installed alongside it in order to work, and you want to test that the needed DLL is correctly installed if it’s missing, you need to be sure that it wasn’t left behind from a previous test, perhaps of a different version of the software.

But build systems aren’t always treated the same way, so malware that specifically targets the build process can cause an enormous and hard-to-find headache.

When developers become “trusted malware spreaders”

Ten years ago, a virus called W32/Induc-A spread widely around the world, and took months to get rid of, precisely because it targeted software developers to turn them into “trusted spreaders”.

The Induc malware only actively infected your system if you had the Delphi compiler installed, otherwise it just sat there quietly, doing very little to draw attention to itself.

If you were a Delphi developer, however, the virus rewrote one of the source code files that was part of the build system itself.

The result was that any program you compiled thereafter would be infected with the malware, but it wouldn’t show its hand again until the newly-compiled program was installed on another developer’s computer.

Ironically, in many companies with in-house development teams, this temporarily turned traditional security advice on its head, because Delphi software built internally was as good as guaranteed to be infected, whereas even unknown and untrusted software downloaded from random sites on the internet had at least some chance of being clean.

In a similar sort of two-stage attack, the infamous Stuxnet virus affected industrial control devices (allegedly, the centrifuges in Iran’s uranium enrichment plant at Natanz) by infecting the computers on which the control sofware was built and downloaded to the devices themselves.

What to do?

We updated our own installation of Xcode as soon as we received the security advisory.

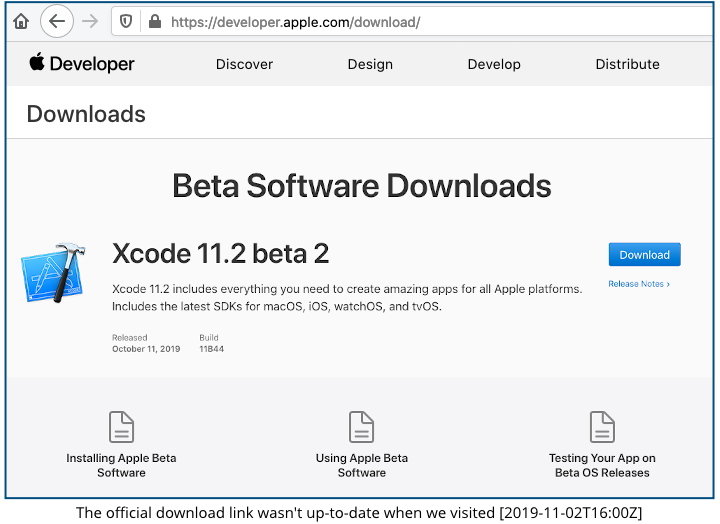

Unfortunately, it wasn’t quite as easy as suggested in the the advisory email, which told us to visit https://developer.apple.com/xcode/downloads/, where we found only the beta 2 version of Xcode 11.2 [2019-11-02T16:00Z]:

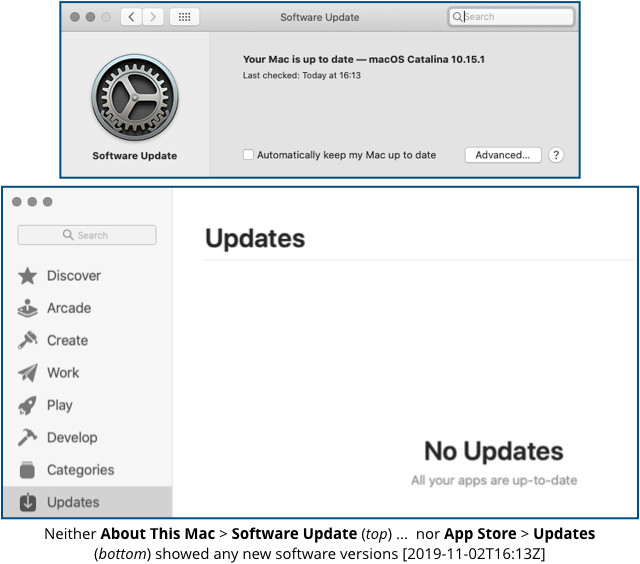

Neither About This Mac nor the App Store showed any updates for us, either, with the former assuring us our macOS was up-to-date, and the latter showing no updates outstanding for any of our installed apps [2019-11-02T16:13Z]:

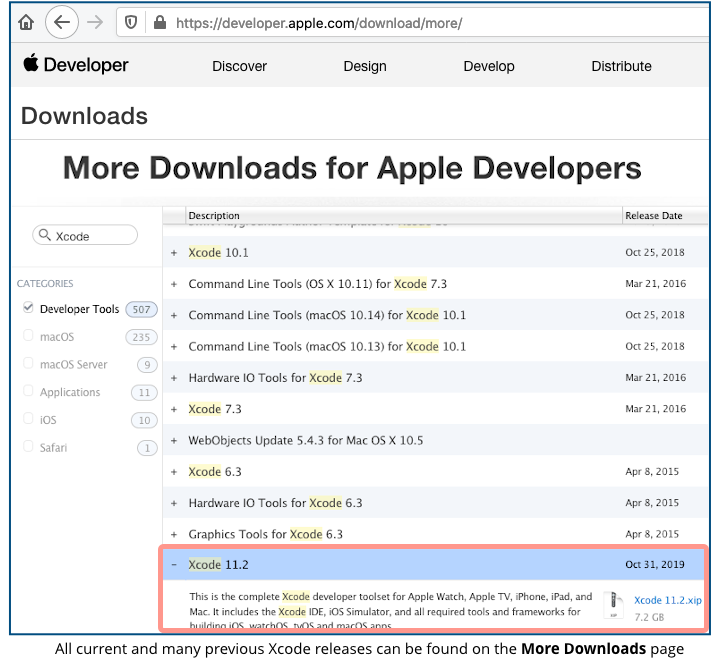

In the end, visiting https://developer.apple.com/download/more/ and searching for Xcode took us to our goal:

If you’re an Apple developer, we suggest you do the same.

Article source: http://feedproxy.google.com/~r/nakedsecurity/~3/FxxcQ0wOZOo/