Boffins demo passwords even users don’t know

What if you could use a password with 38 bits of entropy without memorizing it? Stanford University researchers think they’ve found a way to deliver.

Their argument is that attackers can steal passwords from ill-defended servers, install keyloggers in drive-by attacks, or force people to hand over their security tokens. The aim is to defeat the “rubber hose” attack (ie, beating the information out of some unfortunate insider) – since you can’t divulge what you don’t know.

In a paper to be presented at the August Usenix conference in Washington, Stanford University scientists led by Hristo Bojinov designed a game to deliver a password that the user can remember without knowing it.

The researchers apply a neuroscience concept called implicit learning to the question of cryptography. Activities such as bike-riding or guitar-playing are learned by repetition: people know they’re learning, but they’re not conscious of the processes by which they learn.

The same applies, the researchers say, to repetitive game-playing. While complex games pose explicitly intellectual challenges, there are plenty of games in which the only way to get better is to keep trying.

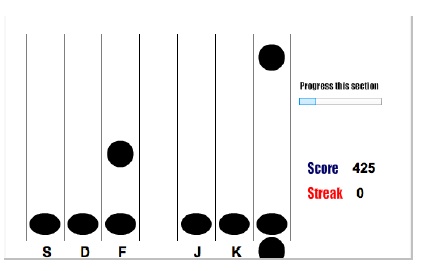

To turn this into a crypto technique, the researchers created a game into which they planted patterns – what the paper refers to as Serial Interception Sequence Learning. The game itself is simple: you use keystrokes to intercept falling blobs before they reach a sink at the bottom of the screen (see image).

Beat the game to get your password. Source: Hristo Bojinov, bojinov.org

However, unlike a “real” game – in which the column in which the blobs appear would be randomized – the researchers embedded a pattern into the game which represented passwords, but couldn’t be memorized. “All of the sequences presented to the user are designed to prevent conspicuous, easy to remember patterns from emerging,” the paper states. The sequences “are designed to contain every ordered pair of characters exactly once, with no character appearing twice in a row”.

What they found was that users could be trained to “beat” the game (and thus capture the password) in between 30 and 45 minutes without ever knowing the password they used – and that even after an interval of two weeks, people would remember how they played.

Of course, the system is still vulnerable to a hack: if attackers gained access to the authentication system itself, all bets are off. And a 30-minute learn time to achieve a password is impractical in the real world. However, the researchers told New Scientist that “If the time required for training and authentication can be reduced, then some of the benefits of biometrics, namely effortlessness and minimal risk of loss, can be coupled with a feature that biometrics lack: the ability to replace a biometric that has been compromised.” ®

Article source: http://go.theregister.com/feed/www.theregister.co.uk/2012/07/19/neuroscience_as_password_protector/