British food writer and activist Jack Monroe has had her bank account drained by hijackers, despite using two-factor authentication (2FA) to protect accounts.

On Friday, Monroe tweeted that her phone number had been SIM-jacked: hit with SIM swap fraud that enabled a hijacker to take over her phone number, intercept the codes sent for the 2FA she says she uses on all her accounts, and drained her accounts of what appeared, at least initially, to be about £5,000 ($6,350) – a figure that could rise.

The self-employed freelancer, who says she has to hustle “for every pound I earn,” said that her card details and PayPal information were apparently intercepted during an online transaction. Meanwhile, her phone number was ported to a new SIM card, Monroe said.

SIM swap fraud is one of the simplest, and therefore the most popular, ways for crooks to skirt the protection of 2FA, according to a warning that the FBI sent to US companies last month.

How the crooks swing a SIM swap

As we’ve explained, SIM swaps work because phone numbers are actually tied to the phone’s SIM card – in fact, SIM is short for subscriber identity module, a special system-on-a-chip card that securely stores the cryptographic secret that identifies your phone number to the network.

Most mobile phone shops out there can issue and activate replacement SIM cards quickly, causing your old SIM to go dead and the new SIM card to take over your phone number…and your telephonic identity.

That comes in handy when you get a new phone or lose your phone: your phone carrier will be happy to sell you a new phone, with a new SIM, that has your old number.

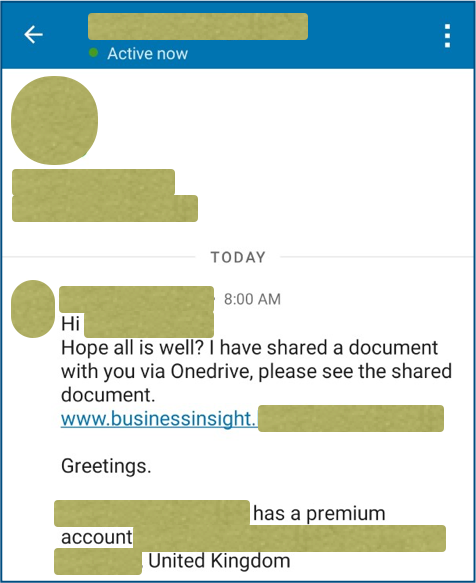

But if a SIM-swap scammer can get enough information about you, they can just pretend they’re you and then social-engineer that swap of your phone number to a new SIM card that’s under their control.

By stealing your phone number, the crooks start receiving your text messages along with your phone calls, and if you’ve set up SMS-based 2FA, the crooks now have access to your 2FA codes – at least, until you notice that your phone has gone dead, and manage to convince your account providers that somebody else has hijacked your account…

…which, hopefully, Monroe can do.

On Tuesday, she said that so far, she’s “played nicely” because she wants her phone number and money back, but that as soon as she gets them, she’s “going to town on both my phone provider and bank for allowing this to happen.”

Valuable PII posted publicly

Monroe said that at least one type of identity verification information – her birthdate – is publicly available, in her Wikipedia entry, so there’s no obfuscating that. (Though those of us who aren’t public celebrities with Wikipedia pages should at least try to keep that personally identifiable information [PII] out of the public eye.)

She pre-empted potential cybersecurity finger-wagging by pointing out that she doesn’t use publicly available email addresses on her financial accounts and that her passwords are “gobbledegook letters and numbers and special characters” – in other words, she’s using proper, tougher-than-nails, and, one assumes, unique passwords.

(If you need to know how to cook up such passwords, please do read this. If you reuse the same password(s), please don’t. Here’s why it’s a bad idea.)

What to do?

When it comes to avoiding SIM swap fraud, Paul Ducklin has useful tips, and they’re certainly worth repeating now:

Watch out for phishing emails or fake websites that crooks use to acquire your usernames and passwords in the first place. Generally speaking, SIM swap crooks need access to your text messages as a last step, meaning that they’ve already figured out your account number, username, password and so on.

Avoid obvious answers to account security questions. Consider using a password manager to generate absurd and unguessable answers to the sort of questions that crooks might otherwise work out from your social media accounts. The crooks might guess that your first car was a Toyota, but they’re much less likely to figure out that it was a 87X4TNETENNBA.

Use an on-access (real time) anti-virus and keep it up-to-date. One common way for crooks to figure out usernames and passwords is by means of keylogger malware, which lies low until you visit specific web pages such as your bank’s logon page, then springs into action to record what you type while you’re logging on. A good real time anti-virus will help you to block dangerous web links, infected email attachments and malicious downloads.

Be suspicious if your phone drops back to “emergency calls only” unexpectedly. Check with friends or colleagues on the same network to see if they are having problems. If you need to, borrow a friend’s phone to contact your mobile provider to ask for help. Be prepared to attend a shop or service centre in person if you can, and take ID and other evidence with you to back yourself up.

Consider switching from SMS-based 2FA codes to codes generated by an authenticator app. This means the crooks have to steal your phone and figure out your lock code in order to access the app that generates your unique sequence of logon codes.

Having said that, switching from SMS to app-based authentication isn’t a panacea.

Malware on your phone may be able to coerce the authenticator app into generating the next token without you realizing it – and canny scammers may even phone you up and try to trick you into reading out your next logon code, often pretending they’re doing some sort of “fraud check”.

If in doubt, don’t give it out!

Article source: http://feedproxy.google.com/~r/nakedsecurity/~3/QJiDHTqtHDo/

Check out The Edge, Dark Reading’s new section for features, threat data, and in-depth perspectives. Today’s top story: “14 Hot Cybersecurity Certifications Right Now.“

Check out The Edge, Dark Reading’s new section for features, threat data, and in-depth perspectives. Today’s top story: “14 Hot Cybersecurity Certifications Right Now.“

Check out

Check out