Dell’s risky “Superfish-style” security certificates – here’s what to do

Remember the Superfish controversy?

Computer vendor Lenovo shipped a range of laptops with a preinstalled application called Visual Discovery from a marketing company called Superfish.

Visual Discovery peeked at your web traffic, extracted images, and tried to figure out what you were interested in so it could send you related and relevant ads.

Sort of like what Google and others do with text (by looking at your searches, your webmail, and so on), but using images instead.

Unfortunately, Superfish decided it would be neat to look inside your secure web traffic (HTTPS) as well, which means:

- Intercepting encrypted connections from your browser.

- Connecting to the encrypted website on your behalf. (What’s known as proxying.)

- Decrypting the returned content in order to analyse it.

- Re-encrypting it.

- Passing it to your browser, which expects an encrypted reply.

But this causes one of two problems:

- Either the encrypted reply to the browser is marked as coming from Superfish, not from the official site.

- Or Superfish pretends to be the official site, and the encrypted reply has a suspicious digital certificate.

By default, both of these behaviours lead to a certificate warning in the browser, for every encrypted site.

LET’S PRETEND

The usual solution is for your browser to agree to trust “pretend” digital certificates from Superfish, or whoever else is acting as the so-called man-in-the-middle (MiTM), so that the MiTM can represent itself as any site it likes.

Typically, this is done by adding what’s known as a trusted root certificate to the browser or the operating system, authorising some intermediary program to take over encryption duty, so to speak, on behalf of all encrypted sites.

When the intermediary is a secure gateway or web filtering server, your computer only needs the trusted certificate and its public key, the part that lets you verify who signed the certificate.

The private key – the part that actually signs the “pretend” certificates in the first place – is stored on the gateway and protected strongly.

Of course, if the MiTM is actually runnning on every computer in your network, each computer needs a copy of the trusted certificate, its public key, and its private key, because the “pretend” certificates will be both signed (private key) and verified (public key) right there on the same computer.

That was the case with Superfish, and it created a security risk, because, generally speaking, private keys are more vulnerable to theft by malware on a general-purpose computer like a laptop than on a server locked away in the network room.

In fact, in the Superfish case, it created a giant security risk, because every computer had a copy of exactly the same private key, protected with exactly the same password, and the password was trivial to extract from the Superfish software.

Indeed, the password was the name of the third-party software company that created the software component used for the MiTM functionality.

Therefore every crook in the world suddenly knew how to issue “pretend” certificates for fake websites that would pass muster on any computer with the Superfish software installed.

Clearly, this opened a serious and non-obvious security hole, not least because a crook could have created “pretend” certificates to masquerade as your webmail service or your bank.

We showed you how to get rid of the offending trusted root certificate in the Superfish case, and how to remove the poorly-written Superfish MiTM software as well.

Problem solved.

MORE RISKY CERTIFICATES

Fast forward from February 2015 to November 2015, and this time, it’s Dell laptops at risk.

It seems that two Dell-issued trusted root certificates have been reported “in the wild” in the past few days, which show up in the Windows Certificate Manager as:

- eDellRoot

- DSDTestProvider

Dell has officially commented on the first of these, admitting its mistake, explaining how to remove the offending certificate by hand, and promising a software update that will remove it automatically, just in case.

We assume that the second certificate can be removed using similar instructions, and that it too will soon vanish anyway via an automatic security update. (We don’t have an affected Dell laptop handy to test this.)

Ironically, Dell says that the eDellRoot certificate “was intended to provide the system service tag to Dell online support allowing us to quickly identify the computer model, making it easier and faster to service our customers.”

Why this needed a private key – the very same private key, apparently password protected with the decryption key dell – on every computer isn’t clear, but Dell’s prompt response is nevertheless appreciated.

It seems that the DSDTestProvider certificate has a similar sort of back-story, as it is apparently installed if you use the Dell System Detect (DSD) software that is supposed to help you figure out what hardware you have.

WHAT TO DO?

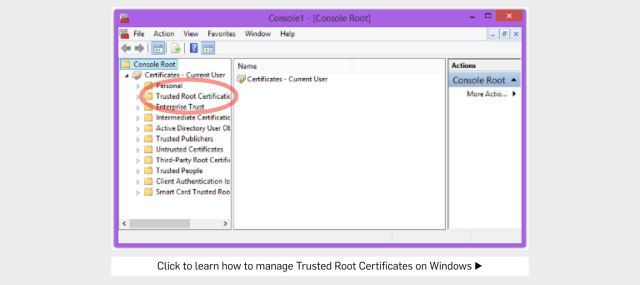

Follow the instructions provided by Dell, which are similar to the ones we issued back when Superfish was in the news, to use the Windows Certificate Manager to remove the abovementioned trusted root certificates.

It’s worth learning how to use the Certificate Manager anyway, even if you don’t have an affected Dell product…

…just in case this sort of thing happens again.

Article source: http://feedproxy.google.com/~r/nakedsecurity/~3/xKvdnLSL-8w/