Hackers blamed for unusual tweets from Jeremy Clarkson, Columbian FARC rebels

TV presenter Jeremy Clarkson and Colombian militia group FARC may not have much in common, but this week they were linked by headlines blaming hackers for potentially embarrassing Twitter messages.

TV presenter Jeremy Clarkson and Colombian militia group FARC may not have much in common, but this week they were linked by headlines blaming hackers for potentially embarrassing Twitter messages.

The ever-controversial Clarkson found himself once again in hot water earlier this year when he was accused of using a potentially offensive racial epithet in an episode of wildly popular TV motoring show Top Gear. He was later found by an inquiry to have “breached broadcasting rules by including an offensive racial term”.

This week, the same ambiguous term appeared in a tweet from Clarkson’s account, which has since been deleted. Follow-up tweets from Clarkson insisted that the offensive post had not been made by him, implying that some unnamed third party had gained access to his account.

Meanwhile far away in Colombia, a tweet appeared on the account of the peace negotiating team of Marxist-Leninist rebel organisation FARC-EP, claiming that a kidnapped general was a prisoner of war.

According to Reuters, the group later denied responsibility for the tweet, claiming the account had been hacked. Once again no details of the identity or agenda of the alleged hackers were given.

It’s not clear who was really to blame for these tweets, but mysterious and apparently all-powerful “hackers” have become something of a general-purpose scapegoat these days, a convenient hook on which we can hang blame for any transgression or blunder, and a term the press can invoke to explain any kind of computing surprise or upset.

In the old days it was generally malware which took on this role, notably in the epic San Diego firework fiasco; the tendency, and its lack of basis in fact, have been graphically illustrated by both XKCD and Redditors.

Now hackers are the go-to excuse, often with a similar paucity of evidence. An earlier case involved singer Alicia Keys, crying hack to cover apparent betrayal of a sponsor.

Of course, in many cases it’s clear that accounts have indeed been hijacked and used for purposes their real owners would have no reason to pursue – the many takeovers claimed by the Syrian Electronic Army and Anonymous being prime examples.

But all too often we use the term “hack” to signify any kind of unwanted computer-related activity, in many cases something as basic as knowing or guessing someone’s password, surely the most rudimentary variety of “hacking” possible.

The use of social engineering to trick people into revealing user IDs and passwords takes this up a notch or two, which makes the likes of the SEA and the people behind Celebgate more appropriate for the hacker designation.

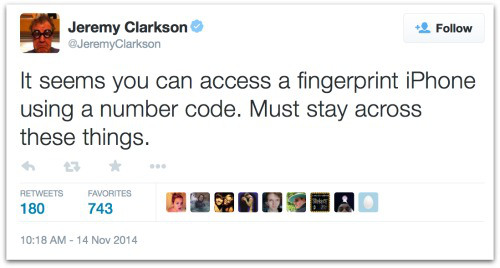

Clarkson’s later Twitter messages indicated that his iPhone had been accessed using the PIN code to unlock it, a method which he had apparently assumed was unavailable with fingerprint unlocking enabled.

It seems you can access a fingerprint iPhone using a number code. Must stay across these things.

This would seem to imply that his “hacker” had physical access to his phone, and knew or guessed his PIN code. So, not so much of a hacker, more likely a friend or acquaintance pulling a rather poorly-judged prank. Clarkson himself did not invoke the hacker term, but it appears in most headlines on the story.

It’s not clear whether any real hacking was involved in the FARC case, or if it’s just another instance of passing the buck onto a vague and untraceable enemy, but the point remains.

The hacker has become the bête noire of the modern world, thanks to repeated exposure in the never-ending flood of data breaches and celebrity embarassments, and is now available as a catch-all excuse for anything we don’t want to take responsibility for ourselves.

But we tend to forget that in blaming others and claiming our security has been breached, we are in fact admitting our own failure to properly secure our accounts.

With proper use of strong passwords, two-factor authentication options, and caution and awareness of social engineering scams, it shouldn’t be so easy for others to access our stuff or send out messages in our names.

But then, of course, we wouldn’t have such a convenient cover for our own mistakes.

Follow @VirusBtn

Follow @NakedSecurity

Image of Jeremy Clarkson courtesy of Featureflash / Shutterstock.com.

Article source: http://feedproxy.google.com/~r/nakedsecurity/~3/B9taNo7hQ4g/