How one man could have flooded your phone with Microsoft spam

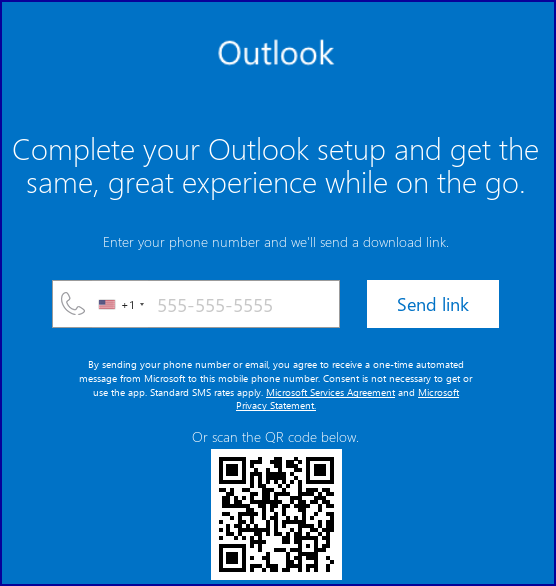

Microsoft has a neat web page that helps you get Outlook set up on your phone.

You can either scan in a QR code off the web page, which takes you to the relevant download link…

…or put in your phone number and get an SMS with the link in it:

Just like Italian security researcher Luca Epifanio, our first thought was, “What if someone decides to put in someone else’s phone number and then spam them over and over and over again?”

That would be pretty darned bad – bad for the recipient, whose phone would be swamped with unwanted text messages, and bad for Microsoft, who would look like shabby and unreconstructed spammers.

(It might also end badly for the person who dishonestly triggered all the spam in the first place, if ever they were found by law enforcement or the regulators, but that is an issue for another day.)

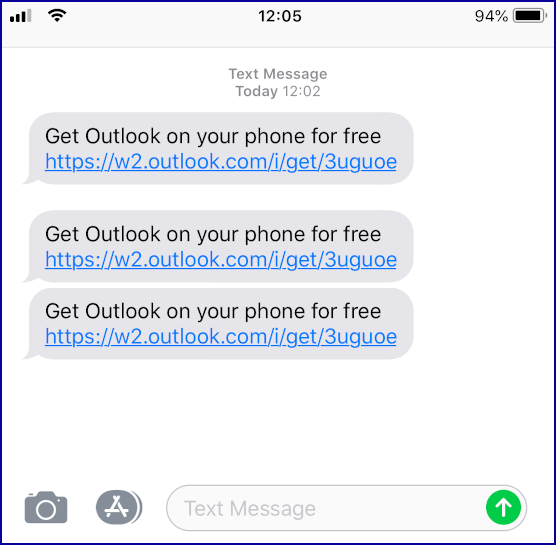

We tested it against our own phone number, using various browsers from various countries (we used the Tor proxy so we emerged onto the internet from semi-random places), and were happy to notice, as did Luca Epifiano, that after three messages, that was that.

Microsoft’s website will accept the number a fourth, fifth, sixth time, and so on, but simply and quietly stops texting it once it’s received three messages. (We don’t know how long it takes for the block to be lifted, but it certainly stopped us spamming ourselves at will.)

Only the first three showed up.

Well, Luca wondered just how robust Microsoft’s “same number” detection might be, and whether it could easily be bypassed.

Using a locally-installed web proxy, he snooped on his own web traffic to see what the data looked like on the way from his browser to Microsoft.

To his surprise, he found that by replaying the original web request with a non-alphabetic character at the end, such as a star (*) or a plus (+), he’d get three more goes at texting the number.

Then he could pick another character and get three more goes, and so on, allowing him to bypass the three-message limit at high speed, just by churning out new HTTP requests with a tiny modification each time.

Only the digits matter in the phone number to which the message gets sent, but – as Luca suggested in an email he sent us – it looks as though Microsoft’s “number verification” check was done with the extraneous characters included.

In other words, the number wasn’t being trimmed to its simplest correct form (you’ll see this called canonicalisation in the jargon) before it was logged, tested and used.

As a result, numbers that were the same in practice appeared different in theory, allowing the rate limit to be bypassed.

This is a similar sort of problem to one that Google experienced back in 2017, when an adware app that falsely claimed to be from the vendor WhatsApp, Inc. was able to sneak past the Play Store validation checks simply by adding a space character to the company name.

Visually, you couldn’t tell the difference, so the new app looked legitimate, but programmatically the two company names were of different lengths and contained different characters – so the new app was not recognised as an imposter and was admitted anyway.

What to do?

The good news is that you don’t have to do anything – Luca reported this responsibly to Microsoft, who fixed the problem.

We tried adding redundant characters to our own phone number today, and were unable to send any messages after the third had gone through.

Luca also received a bug bounty payout, with the ultimate result that everyone ended up a winner.

We think that the lessons to learn are:

- Bug hunting isn’t just about machine code hacking and reverse engineering. You don’t need to crack open a debugger and a disassembler to do useful and productive cybersecurity work.

- Bugs can be deceptively simple. In this case, a single character that would typically be ignored was enough to bypass an important rate limit. If you’re a programmer, don’t forget to test for the obvious things as well as all those complex “corner cases” you need to deal with.

- Responsible bug reporting really works. If you find bugs, it’s tempting to make a big splash by disclosing them for shock value in a blaze of glory, but as Luca has shown here, you can do the right thing, help everyone else, and still get recognition – without turning security holes into nightmares.

Article source: http://feedproxy.google.com/~r/nakedsecurity/~3/SwdrGrXbCJw/