LinkedIn users sue over service’s “hacking” of contacts and spammy ways

Brian Guan, a Principal Software Engineer at Linkedln (currently on sabbatical) said it all when he described his role on the site:

Brian Guan, a Principal Software Engineer at Linkedln (currently on sabbatical) said it all when he described his role on the site:

Devising hack schemes to make lots of $$$ with Java, Groovy and cunning at Team Money!

Also, LinkedIn’s 2011 10-K [*] identified its key strategy as being to “Foster Viral Member Growth.”

Mind you, the fact that LinkedIn wants to grow virally and make money isn’t terribly surprising, but the way the professional networking site is doing it has now spawned a class action lawsuit.

Four LinkedIn users in the US are suing the company for allegedly “hacking” users’ email accounts, downloading their address books, and then repeatedly spamming out marketing email, ostensibly from the users themselves, to their assumably beleaguered contacts.

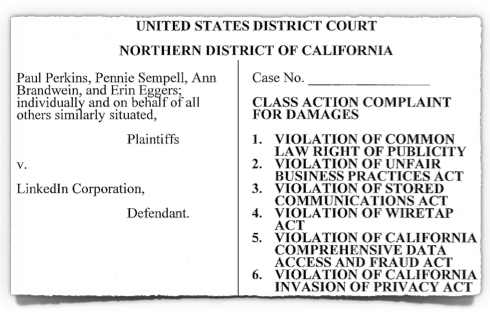

The complaint, filed in US District Court on Tuesday for the Northern District of California, outlines the steps LinkedIn goes through to “hack” into users’ external email accounts and extract email addresses, all without obtaining users’ consent or requesting a password.

First, LinkedIn requires an email address to sign up for the service. Next, it harvests email addresses of anyone with whom the users have ever exchanged email.

The service then sends a total of three emails to a given user’s contacts, including an initial pitch, followed up by two reminder emails if the users don’t sign up for a LinkedIn account.

Each of these reminder emails contains the Linkedln member’s name and likeness so as to appear that the Linkedln member is endorsing Linkedln, and none of them entail notice or consent from the LinkedIn member, the complaint charges:

The hacking of the users’ email accounts and downloading of all email addresses associated with that user’s account is done without clearly notifying the user or obtaining his or her consent. If a LinkedIn user leaves an external email account open, LinkedIn pretends to be that user and downloads the email addresses contained anywhere in that account to LinkedIn servers.

The LinkedIn users who filed the complaint are Paul Perkins, Pennie Sempell, Ann Brandwein, and Erin Eggers.

Perkins, a New York resident, formerly served as manager of international advertising sales for The New York Times, the complaint says.

Brandwein is a statistics professor at Baruch College in New York. Eggers is a film producer and former vice-president of Morgan Creek Productions in Los Angeles, and Sempell is a lawyer and author in San Francisco.

The quartet acknowledge that in the complaint that LinkedIn asked for permission to “grow” their networks, but they claim that the service never said it would send a series of email invitations to their contacts.

In fact, it’s only Google that gives Gmail users a heads-up that downloading is going on, the complaint states (all four LinkedIn users on the complaint are also Gmail users):

In cases where the user’s external email account is a Google Gmail account, a Google screen pops up stating, “Linkedln is asking for some information from your Google Account.” … The Google notification screen, however, does not indicate that Linkedln will download and store thousands of contacts to Linkedln servers. Rather, this notification screen misleadingly states that Linkedln is asking for “some information.” Linkedln does not provide this notification to its users; it is Google that provides this screen.

The complaint notes that LinkedIn’s site contains hundreds of complaints linked to the practice.

The plaintiffs are accusing LinkedIn of violating the federal wiretap law as well as California privacy laws, and are seeking class-action status.

LinkedIn users, are your friends complaining about LinkedIn’s sending spam under your name and photo?

Would you sign up for the suit, or do you instead consider LinkedIn’s process just the cost of getting a free service?

And furthermore, what do you think of the word “hacking” with regards to LinkedIn’s alleged practices? It sounds more like “marketing” to me, but that all boils down to semantics.

Let us know what you think in the comments below.

[*] US companies submit Form 10-K reports each year to the Securities and Exchange Commission, giving detailed information about corporate performance, finances and so forth.Article source: http://feedproxy.google.com/~r/nakedsecurity/~3/8XNVVkkzD_Y/