Making phishing more complex

Earlier this week a colleague pointed out an intriguing phishing sample that he had come across.

Earlier this week a colleague pointed out an intriguing phishing sample that he had come across.

It was interesting not because of any great sophistication or complexity, but rather that it illustrated the reuse of an old social engineering trick.

The brand being targeted in the phish campaign is Poste Italiane, a well known Italian group that includes financial and payment services in its product portfolio.

We see numerous phishing attacks targeting this group each month, with attackers keen to trick their customers into unwittingly submitting their credentials to fake login sites.

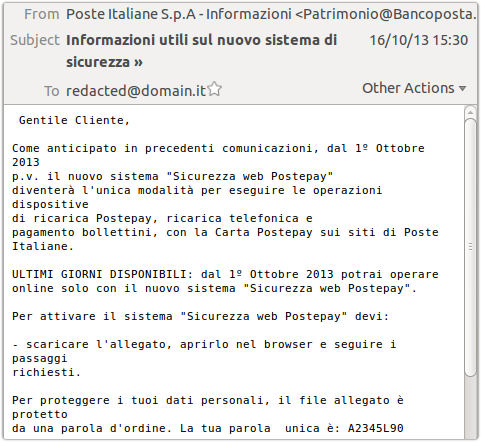

This latest attack takes a similar strategy to many recent phish campaigns, where the email contains a HTML attachment which the recipient is enticed into opening.

From: “Poste Italiane S.p.A – Informazioni”

Attachment: scarica.html

The typical social engineering to entice the user into opening the attachment is evident:

To activate the “Security web Postepay ” you need to:

– Download the attachment, open it in the browser and follow the steps requested.

Curiously, there is reference to some password protection within the attachment, and a password is provided in the message body:

To protect your personal information, the attached file is protected by a password. Your word is unique: A2345L90

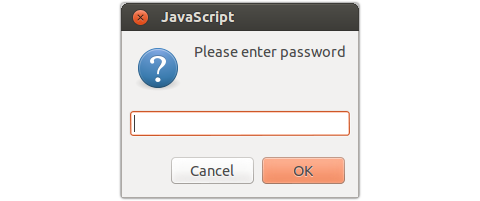

Sure enough, recipients tricked into opening the HTML attachment will be prompted for a password:

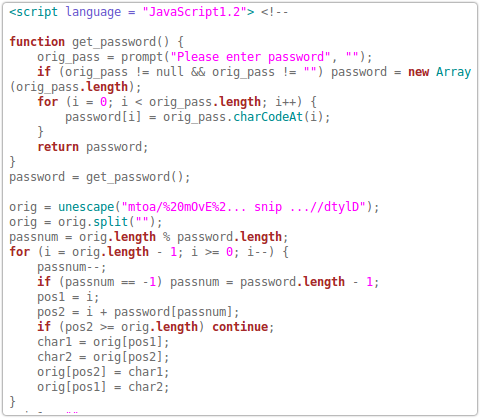

Inspecting the HTML attachment reveals the code behind this – simple JavaScript to prompt the user for a password, which is then used to decode a string:

If the recipient types in the correct password (A2345L90 in this example), the string is decrypted and written back to the page:

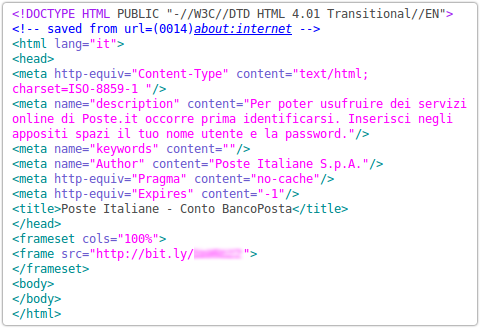

This then loads the phish page via the frame, which references a bit.ly shortened URL:

So, all in all, nothing hugely exciting and definitely not new. (The infamous Bagle virus, which was widespread 10 years ago, mailed itself out in password-protected archives.)

So why bother using the password?

One possible answer is that is prevents security scanners seeing the HTML of the phish page or, as in this case, the HTML that loads the phish page.

This is true, although I would argue that the JavaScript used to prompt for and use the password is more unusual than simple non-obfuscated HTML.

Another possible answer relates to the expectations of the recipient.

Adding the password into the mix might be expected to make the attacks less successful: it imposes an additional barrier to the attack, since blindly double-clicking the attachment is no longer enough.

But for some users, the presence of the password may actually strengthen the social engineering of the phish, by lending it an air of security and credibility.

Within the ivory towers of SophosLabs, it is easy to think that users are attuned to the risks of email attachments.

The proliferation of email-borne phishing and malware attacks suggests this is not the case.

Sufficiently many users seem still to be falling for the same old tricks – enough for the attackers to turn a profit, at any rate.

One thing is for certain: the criminals behind the ongoing phishing campaigns against Poste Italiane are here to stay.

Article source: http://feedproxy.google.com/~r/nakedsecurity/~3/TXvC120xZ2M/