Mamba ransomware strikes at your whole disk, not just your files

Thanks to Andrew O’Donnell and Dorka Palotay of SophosLabs for thir behind-the-scenes work on this article.

Here’s a new ransomware strain that SophosLabs brought to our attention.

It’s named Mamba (Sophos products block it as Troj/Mamba-A and Troj/Mamba-B), after the deadly snake of the same name.

The good news is that we’ve not seen Mamba in the wild; it’s not very well-written or reliable; and it’s not entirely clear how the crook or crooks behind it plan to make any money out of it.

The bad news is that if you do get infected by mistake, you might not be able to recover your computer at all, even if you are willing to negotiate with the crooks.

Nevertheless, Mamba is interesting because the creators quite clearly set out to try something a bit different and see what happened.

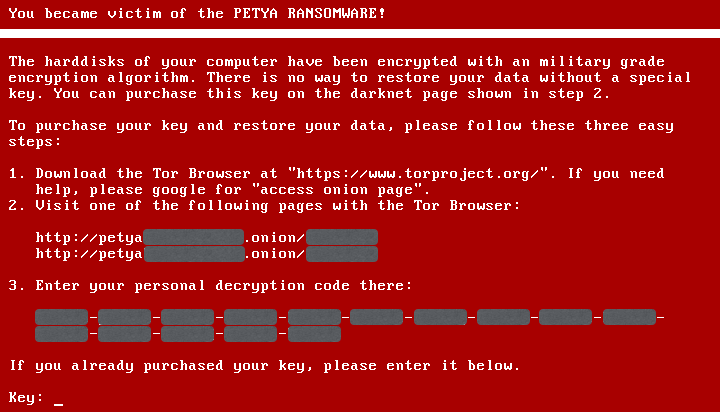

We’ve already seen ransomware called Petya that scrambles the master index of your hard disk (what’s known as the Master File Table or MFT), instead of going after individual files, leaving your computer unbootable and stuck at a 1990s-style boot screen that tells you how to buy your way out of trouble.

Petya left the bulk of your raw data unscrambled at the sector level, albeit tantalisingly out of reach.

Mamba takes the approach of ransoming your whole disk one step further: it scrambles every disk sector, including the MFT, the operating system, your apps, any shared files and all your personal data, too.

Ironically, Mamba does all of this with very little programming effort: the malware simply installs and activates a pirated copy of the open source software DiskCryptor.

DiskCryptor isn’t a replacement that has sprung up since the demise of TrueCrypt in 2014. In fact, the most recent version of DiskCryptor dates from just two months after the TrueCrypt developers killed off their product, and the DiskCryptor website still compares itself with the long-defunct TrueCrypt.

DiskCryptor is what’s known as a Full Disk Encryption (FDE) tool, like Microsoft’s BitLocker or Apple’s FileVault, that asks for a password at bootup, and then decrypts every sector as it is read in and encrypts every sector as it is written out.

Once you’re in, you’re into everything, so FDE doesn’t control access to individual files (you need an application such as Sophos SafeGuard Encryption that can deal with both disks and files for that), but FDE is nevertheless a great way of securing your laptop against loss or theft.

If crooks steal your laptop while it’s turned off or securely locked, your whole disk is just so much shredded cabbage to them, so even if they graft your hard disk into another computer, or boot from a Linux-based recovery CD or USB, the contents are off limits.

Of course, in this case, the crooks are turning FDE against you, because they know the DiskCryptor password, and you don’t.

How Mamba infects

We haven’t seen any Mamba samples in our email traps, so we can’t tell you any specifics to look out for, assuming the crooks use email to distribute the threat, as is common for ransomware attacks these days.

As usual, though, be especially cautious of the sort of email you often open routinely when you’re going through your business emails each morning: invoices, payment advice, requests for quotation and so forth.

Ransomware crooks have found this sort of email a tempting and effective lure to attack home users and businesses alike.

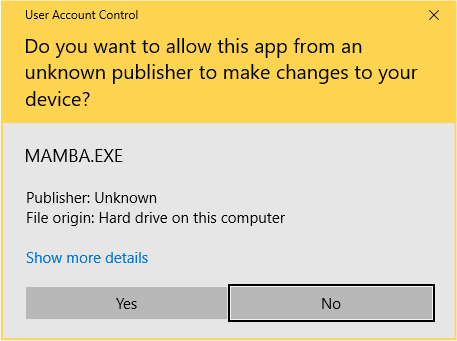

If you do run an infected file by mistake Mamba doesn’t seem to do much, though you will see an “elevation” prompt first asking you to give the unknown app permission to do more-dangerous-than-usual stuff.

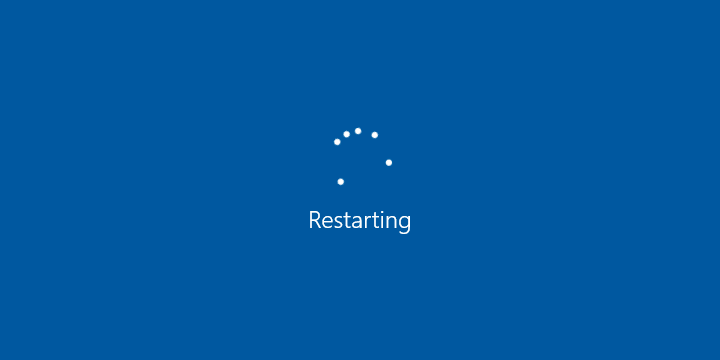

After a short while, your computer will spontaneously reboot, which you can think of as your second red flag:

Before rebooting, the Mamba program surreptitiously installs itself as a Windows service with the name DefragmentationService and with LocalSystem privileges.

Malware running as a LocalSystem service activates even when no one’s logged on, is invisible from the Windows desktop, and has almost complete control over the local computer.

Notably, Mamba has the credentials to install a low-level FDE program like DiskCryptor quietly in the background, which is exactly what it does after rebooting.

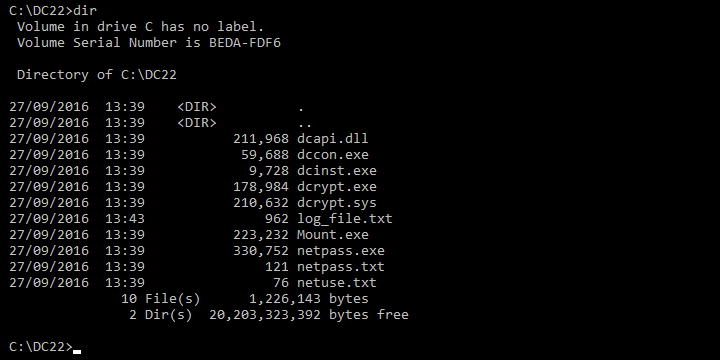

In fact, Mamba carries around with it a regular copy of DiskCryptor, which you can find in the directory C:DC22 after the unexpected reboot:

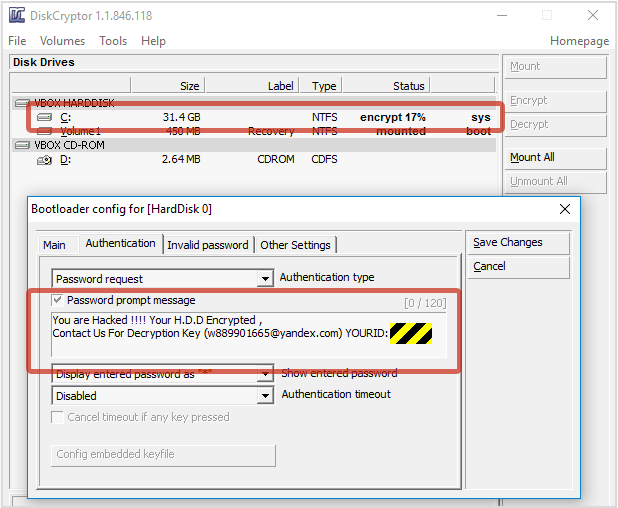

Indeed, you can use the DCRYPT.EXE utility to see what’s happening in the background, as we did here:

You can see that the encryption is progressing steadily (the process typically takes from tens of minutes to several hours, depending on the size of the disk and the speed of the computer).

You can also see that the crooks have preconfigured their deployment of DiskCryptor to give you rudimentary “how to pay” instructions instead of a more conventional password prompt.

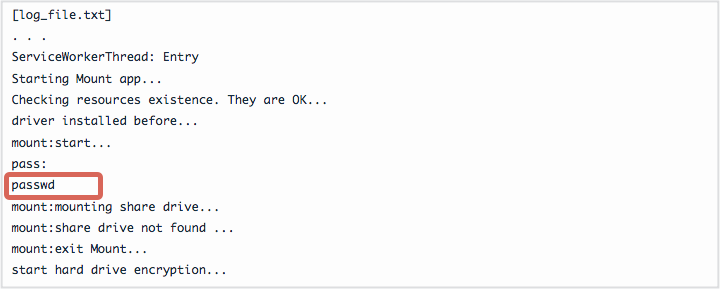

Once the encryption finishes, you’re in a handy, if rather tricky position: your computer doesn’t reboot automatically, so all your files are still accessible, and the DiskCryptor log, contained in the file log_file.txt contains the actual plaintext password:

Usually, we’d be deeply critical of software that dumps personal, private or secure data into plaintext logfiles, but in this case it’s a lifeline: you can use the Decrypt option in the DCRYPT utility to undo the encryption!

If you don’t realise that the background encryption has happened, of course, you’re in trouble next time you reboot your computer.

Unfortunately, as we mentioned above, DiskCryptor hasn’t had any development in the past two years, and it’s still incompatible with the way that most modern Windows installations configure your hard disk.

Older operating system versions and older hard disks used a format called MBR, short for Master Boot Record, that allowed four partitions per disk and a maximum disk size of 2 terabytes. These days, most installations use a similar-but-different disk layout called GUID Partition Table, or GPT for short, which supports 128 partitions of sizes up to billions of terabytes.

DiskCryptor’s low-level bootup code, where you’re asked for your password so that your encrypted partitions can be unscrambled in real time and your computer can start up, isn’t compatible with GPT disks.

Mamba, however, installs DiskCryptor anyway.

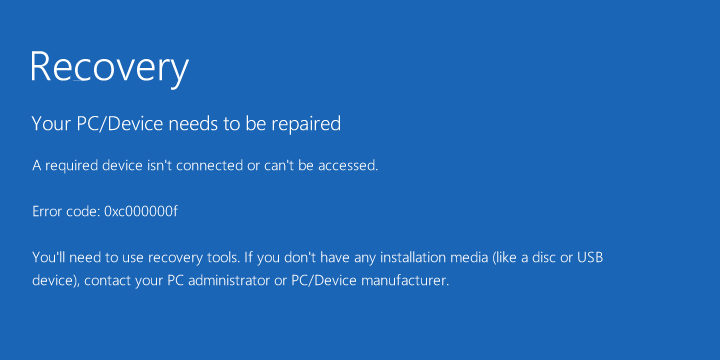

On any currently supported Mac you’ll definitely have a GPT-format disk; on most recent Windows computers, you almost certainly will, so after rebooting you’ll get something like this:

You won’t even see the “how to contact” us message from the crooks, assuming you wanted to get in touch with them.

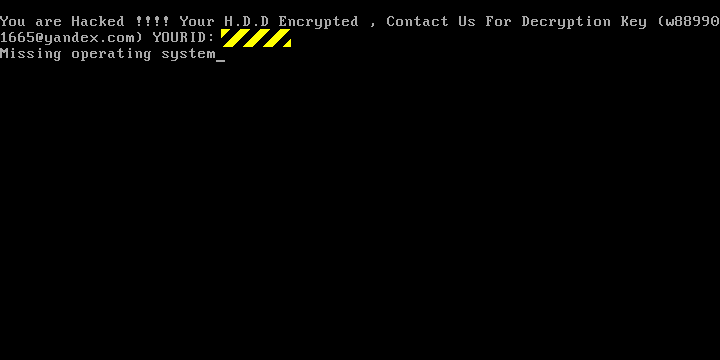

Sadly, the news isn’t much better even if you have an old-school disk configuration: in our tests, we got no further than Missing operating system on our MBR-format disk:

What to do?

We always recommend not paying ransomware crooks if possible, but we’ve never been hard-hearted enough to get on our soap box and say that you’d be wrong to do so, because it’s not our data that’s being held hostage.

In this case, however, we think you’d be wise to write off your data and prepare for a full reinstall. (Next time, perhaps consider using some sort of real-time anti-virus, and consider figuring out a sustainble plan to keep full, offline backups.)

We’re not sure how the crooks keep track of which YOURID goes with what password, or even if they bother to do so.

Also, given how careless the crooks are in installing DiskCryptor when it’s guaranteed to break, we’re not convinced that they could show any sort of “honour amongst thieves” and reliably recover your data even if they wanted to.

So, as always, prevention is way better than cure, not least because in this case there may not actually be a cure, neither for love nor for money.

Here are some links we think you’ll find useful:

- To defend against ransomware in general, see our article How to stay protected against ransomware.

- To learn more about how ransomware works, listen to our Techknow podcast.

LISTEN NOW

(Audio player above not working? Listen on Soundcloud or access via iTunes.)

Follow @NakedSecurity

Follow @duckblog

Article source: http://feedproxy.google.com/~r/nakedsecurity/~3/EAIecjN4UpI/