Ransomware-hit hospital faces second demand despite paying up

We’ve written about the woe of a hospital hit by ransomware before.

In that story, rumours circulated that the amount demanded by the crooks was a whopping 9,000 Bitcoins, or more than $3,000,000.

The CEO of the hospital put paid to the rumour in an official letter that gave the total amount paid as BTC40, or $17,000.

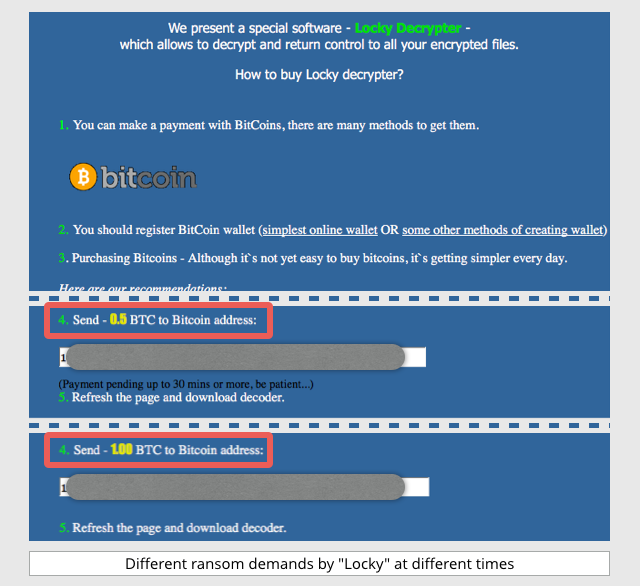

Most ransomware we’ve seen asks for a more affordable amount, typically around BTC 1, or $300-$400, but the demand is often decided at the moment you visit the malware’s “pay page,” rather than hard-wired into the ransomware itself.

That means the crooks can change the amount at any time, or depending on where you live, or any other criterion they like:

Of course, in the Hollywood Hospital case, it’s not impossible that the ransomware affected multiple computers, servers or departments at the same time, and the victims ended up having to pay multiple ransom demands.

Ransomware attacks are often sent out as email attachments in large-scale runs of spam, so any large organisation may well receive many infected emails, directed to many different staff members, at the same time.

Make sure you have a single, well-known phone number or email address where staff are encouraged to report hacking attempts, phishing, suspicious emails, and so on. One vigilant user who puts in a prompt report could warn the rest of your users away from temptation and danger.

Most ransomware deliberately uses a new, randomly-chosen encryption key every time it infects a new computer, to stop victims from helping each other out by sharing their decryption keys.

Now, a new hospital attack has made the news, this time at the Kansas Heart Hospital in Wichita, Kansas.

Apparently, the hospital paid one ransom, but didn’t get all its files back.

A second ransom demand followed, and this time, the hospital didn’t pay up, figuring that was no longer “a wise manoeuvre or strategy.”

What happened?

In most malware-based ransomware attacks, like TeslaCrypt, Locky or Maktub, both the encryption and the presentation of the ransom demand happen automatically, thanks to malware spread widely by email.

Loosely put, the crooks are aiming to make $300 million by calmly taking $300 from 1,000,000 different victims.

You can think of it as a targeted attack in which anyone and everyone is a potential target.

By buying up mailing list data from breached sites (or from unscrupulous mailing list operators), crooks can give even the most widespread and undiscriminating attack a personal flavour that nevertheless makes each email in the spam run a targeted attack of its own.

But crooks can also operate extortion attempts based on encryption in a more traditional way: by hacking into your network, deliberately scrambling databases, changing passwords or deleting vital network configuration settings…

…and then leaving you a very personal message: Pay up, or else.

(Or else try to figure your own way out of the pickle, is what they mean.)

We wrote about an example about this sort of cyberblackmail attack back in 2012, before malware-driven extortion took the world by the throat.

The problem with a directed attack, where the crooks know how to repeat the damage at will even after you’ve paid up, is that it’s much harder to stop them simply coming back for more after you’ve paid the first extortion demand.

We don’t yet know enough to tell whether the Wichita double-ransom attack was down to two concurrent infections with the same encrypting ransomware, thus leaving the hospital with two separate payments to make, or due to a directed hack-and-attack in which the crooks went after the hospital specifically.

What to do?

The good news, at least for the rest of us, is that similar precautions will protect you from malware-driven ransom demands and from what we might call “directed digital blackmail”.

Vital defences in any cybersecurity strategy should include:

- Backup regularly and keep a recent backup copy off-site. There are dozens of ways other than ransomware or cyberblackmail that files can suddenly vanish, such as fire, flood, theft, a dropped laptop or even an accidental delete. Encrypt your backup and you won’t have to worry about the backup device falling into the wrong hands.

- Don’t give yourself more login power than you need. Most importantly, don’t stay logged in as an administrator any longer than is strictly necessary, and avoid browsing, opening documents or other “regular work” activities while you have administrator rights.

- Patch early, patch often. Malware that doesn’t come in via document macros often relies on security bugs in popular applications, including Office, your browser, Flash and more. The sooner you patch, the fewer open holes remain for the crooks to exploit.

For more detailed advice about dealing with attacks of this sort, we’ve published an article entitled How to stay protected against ransomware:

Follow @NakedSecurity

Follow @duckblog

Article source: http://feedproxy.google.com/~r/nakedsecurity/~3/BlQ_Z8r1nm8/