SellHack browser plugin ceases squeezing LinkedIn for hidden email addresses

For a brief window of time that has now slammed shut, a free browser extension called “SellHack” had set off a storm of more-or-less suspicious media reports by promising to “hack” LinkedIn profiles to get at what should be users’ tucked-away, private email addresses.

For a brief window of time that has now slammed shut, a free browser extension called “SellHack” had set off a storm of more-or-less suspicious media reports by promising to “hack” LinkedIn profiles to get at what should be users’ tucked-away, private email addresses.

LinkedIn was not very happy about this.

The professional social network told the BBC earlier in the week that it was doing “everything we can to shut Sell Hack down”, including sending a cease-and-desist letter on Monday.

SellHack bowed to LinkedIn’s command the following day, putting up a blog post titled “The Last 24 Hours” which explained that the SellHack plugin no longer works on LinkedIn pages.

(The post also pointed to how much free publicity this has garnered – the developers got more signups in the past 24 hours than in the 60 days since they’d launched.)

LinkedIn had asked users who downloaded the plugin to “uninstall it immediately”:

LinkedIn members who downloaded Sell Hack should uninstall it immediately and contact Sell Hack requesting that their data be deleted.

Absolutely. I had planned to do that too, but not before hacking my own profile. SellHack has now saved me the trouble.

The plugin was available for Chrome, Safari and Firefox, any of which should ask for permission before plugging in a random extension off the internet.

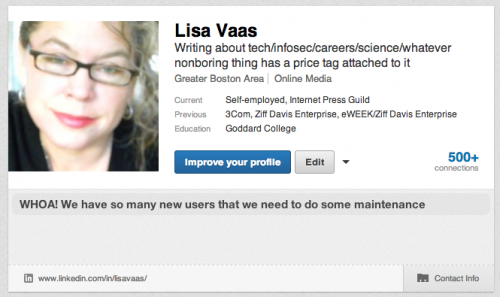

As you can see in the screen grab below, the extension didn’t always deliver the goods. It hit a brick wall with my profile, didn’t deliver my email address, and gave me the excuse that “WHOA! We have so many new users that we need to do some maintenance”.

I tried it on Naked Security’s Mark Stockley and got his email address just fine, after which I dug up email addresses for people both CEO-ish and 99%-ish.

SellHack says on its site that the tool was created for marketing professionals. In its Tuesday post, it says that it’s been described as “sneaky, nefarious, no good, not ‘legitimate’ amongst other references by some.”

They’re not any of that and are in reality far more wholesome, the developers claim:

We’re dads from the midwest who like to build web and mobile products that people use.

In spite of the use of the term “hack” in its name, however, SellHack didn’t actually do any shady hacking of LinkedIn profiles to reveal the email addresses associated with them. Instead it made use of publicly available information on the net combined with “best guesses” and then packaged it all up in a provocative way.

The data we process is all publicly available. We just do the heavy lifting and complicated computing to save you time. We aren’t doing anything malicious to the LinkedIn website.

We haven’t been able to verify this (most of the code was in a publicly hosted library that has now been removed) but it seems the most likely explanation.

A LinkedIn spokesman told the BBC that members should “use caution” before downloading any third-party extension or app:

Often times, as with the Sell Hack case, extensions can upload your private LinkedIn information without your explicit consent.

LinkedIn’s right about downloading dubious plugins. These tiny apps can do a world of cozy things in our browsers, such as help us to watch videos online, view PDF documents or more.

They can also be either malicious or simply out of date and therefore out of touch with a browser’s most recent security vulnerabilities.

Critics have pointed out that LinkedIn itself isn’t innocent of suctioning users’ profile information, mind you.

For example, in February 2014, it pulled the plug on its own “Intro”, an email plug-in for Apple iOS designed to suction LinkedIn profile information and insert it into emails received on phones.

And then too there’s the class action lawsuit charging that LinkedIn gets into users’ private email accounts and sucks out their contact lists – a charge that it denies, or at least, denies doing without users’ permission.

But two – or three or four – wrongs don’t make a right.

Let’s just hope that browser plugin developers see this as a case study in being more transparent, as opposed to a tutorial in getting a lot of free press.

Follow @LisaVaas

Follow @NakedSecurity

Article source: http://feedproxy.google.com/~r/nakedsecurity/~3/E7adZcUF6UQ/