Inside the Check Point Research Team’s Investigation Process

CPX 360 – New Orleans, La. – Security research teams across the industry are always on the hunt for new threats and vulnerabilities so organizations can improve their defenses. But how do these experts decide what to research next? Which issues are of greatest concern to them?

The Check Point Research (CPR) team consists of 150 to 200 people focused on malware analysis and vulnerability research. CPR aims to drive broader threat awareness by discovering and understanding the latest attack techniques, and then sharing them with the industry. The group is divided into two parts: the people who discover new threats and those who investigate them.

In a space as complex and evolving as the modern threat landscape, it can be tough to decide what to research. Maya Horowitz, director of threat intelligence at Check Point, says some work is dictated by analysts’ interests. As an example, she describes one researcher with an interest in linguistics who discovered a cybercriminal from Libya using Facebook to spread malware. She noticed typos in one Facebook post and connected it to others that contained similar mistakes.

Some researchers’ work focuses on problems commonly known within the security industry but rarely discussed outside of it. Horowitz cites malicious mobile apps and cloud misconfigurations as two issues that demand greater public awareness, especially given the growing prevalence of mobile and cloud among consumers and businesses. If someone knows an app from a legitimate store could potentially contain malware, they may think twice before downloading it.

“We are driven by the things that are out there,” she says. In addition to researching common attacks and vulnerabilities, CPR also looks into rarer threats. Malicious files sent to customers in a specific country, for example, may not be a global issue but still merit a CPR investigation.

“In reality, you can’t sell products to defense infrastructures without really knowing how the hacker is working,” says Oded Vanunu, head of products vulnerability research at Check Point.

Vanunu breaks the process down into greater detail: Some researchers are responsible for analyzing infrastructure and sensors, from which they collect logs and raw data that tell them what’s happening on the Internet. “We’re talking millions of logs every hour; billions after one day,” he adds. Analysts dig into this trove of data to spot pattern breaks that could indicate an attack.

“If there are bad actors doing things, we can immediately intercept, we can attack back, or we can decide that we want to see what’s going on,” Vanunu says. These types of anomalies led researchers to discover vulnerabilities in TikTok, Fortnite, and more recently in the Zoom videoconferencing platform. All three investigations began with an unusual level of threat intelligence that led to bug discoveries in each platform.

“Today attacks are very complex,” Vanunu says. “Attacks are different. Attacks require multiple vectors today, moving between technologies. In order to prevent, you need to learn the attack; you need to learn what the attacker is doing.”

What Are You Most Worried About?

The CPR team works with troves of data indicating what attackers are up to, which begs the question: What do they see that is most concerning to them?

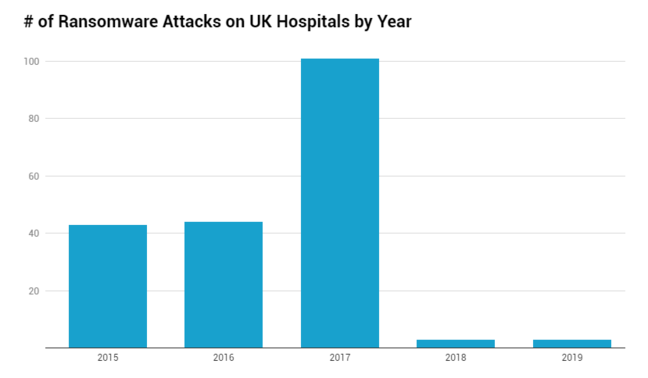

Horowitz first points to the increasing complexity of ransomware attacks. “We do see less ransomware attacks,” she says. “But the ones we are seeing are the more sophisticated ones, targeting companies that have lots of data and lots of money.”

As we’ve seen in the past year, she adds, a target doesn’t have to be a large business to have money or data they fear losing. “They’re not necessarily going after banks, but cities and hospitals that actually don’t invest too much in cybersecurity,” Horowitz continues.

Organizations that fail to adopt the proper tools may also be at risk: While most have invested in traditional security tools, even large enterprises have held back on cloud and mobile security, sandboxing, and other defensive technologies. “A large business might invest a lot in cybersecurity, but not always in the right places,” she says.

For today’s attackers, email is only the first stage of a ransomware attack. Many deploy a botnet and then install Trickbot so they can steal data from target machines and send it back to an attacker-controlled server. This access provides a wide base to deploy a ransomware campaign. Adversaries seek threat intelligence on victims to learn how much money they can demand.

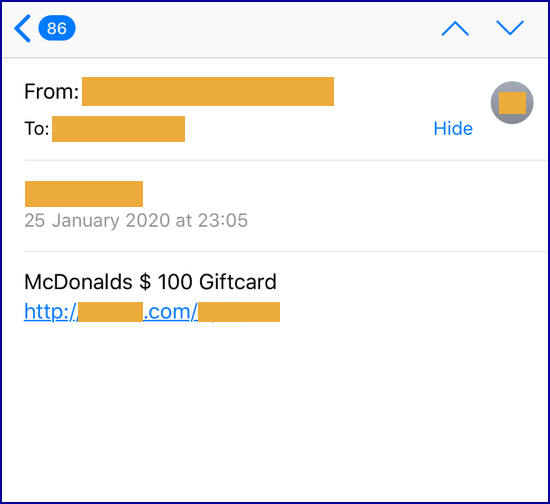

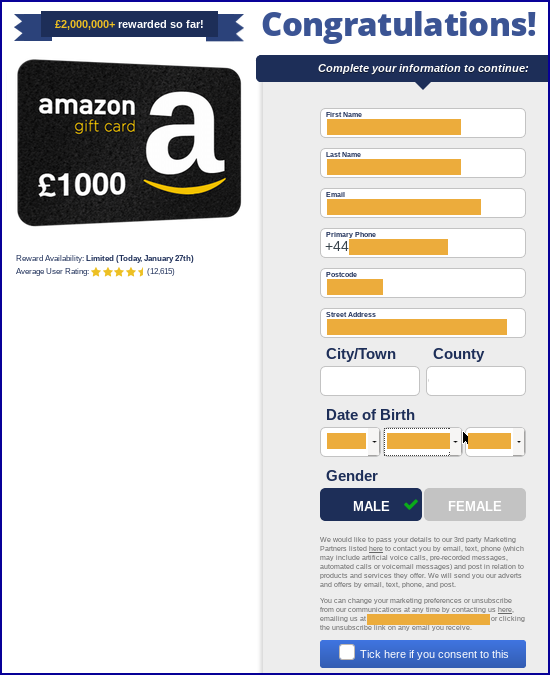

Mobile threats, another concern, are growing more dangerous and pervasive. Attackers have moved beyond pesky adware and clickbait to threats designed for PCs. Adware is annoying, as Horowitz notes, but an info stealer on a mobile device can lift sensitive corporate information. Marketplaces for mobile malware are growing more common, making these threats accessible.

The cloud is evolving as an attack target as companies continue to adopt cloud technologies but fail to improve their security posture to protect the apps they use and develop.

“Everything today is connected to the cloud,” Vanunu says. “One of the worst things we’re seeing, all the time, is that vendors are creating software … and software today is easy to create, but around it are hundreds of APIs.” APIs are used for authentication, encryption, VoIP, statistics, payments, and myriad other tasks. This reliance on APIs means companies depend on software firms to do their job in securing APIs, but “it’s not working like that,” he adds.

Many common apps today are software-as-a-service (SaaS), meaning attackers only need one vulnerability to start moving between users and customers, he continues. Attackers know this, which is why security vulnerabilities are in high demand – and they’re willing to pay big for them. Enterprise cloud applications are in demand, but popular consumer apps could be more lucrative gateways.

“Business cloud applications are less relevant, because if I want to execute an attack, I’ll do it through the application that everyone has,” he explains. This is why vulnerabilities in apps like TikTok are particularly dangerous. At a time when people use the same devices at home and in the office, a consumer vulnerability can give attackers access to a larger pool of targets.

Related Content:

9 Things Application Security Champions Need to Succeed

Assessing Cybersecurity Risk in Today’s Enterprise

How to Manage API Security

Rethinking Enterprise Data Defense

Check out The Edge, Dark Reading’s new section for features, threat data, and in-depth perspectives. Today’s top story: “7 Steps to IoT Security in 2020.”

Check out The Edge, Dark Reading’s new section for features, threat data, and in-depth perspectives. Today’s top story: “7 Steps to IoT Security in 2020.”

Kelly Sheridan is the Staff Editor at Dark Reading, where she focuses on cybersecurity news and analysis. She is a business technology journalist who previously reported for InformationWeek, where she covered Microsoft, and Insurance Technology, where she covered financial … View Full Bio

Check out

Check out