Video It is possible to discern someone’s SSH password as they type it into a terminal over the network by exploiting an interesting side-channel vulnerability in Intel’s networking technology, say infosec gurus.

In short, a well-positioned eavesdropper can connect to a server powered by one of Intel’s vulnerable chipsets, and potentially observe the timing of packets of data – such as keypresses in an interactive terminal session – sent separately by a victim that is connected to the same server.

These timings can leak the specific keys pressed by the victim due to the fact people move their fingers over their keyboards in a particular pattern, with noticeable pauses between each button push that vary by character. These pauses can be analyzed to reveal, in real time, those specific keypresses sent over the network, including passwords and other secrets, we’re told.

The eavesdropper can pull off this surveillance by repeatedly sending a string of network packets to the server and directly filling one of the processor’s memory caches. As the victim sends in their packets, the snooper’s data is pushed out of the cache by this incoming traffic. As the eavesdropper quickly refills the cache, it can sense whether or not its data was still present or evicted from the cache, leaking the fact its victim sent over some data, too. This ultimately can be used to determine the timings of the victim’s incoming packets, and the keys pressed and transmitted by the victim.

The attack is non-trivial to exploit, and Intel doesn’t think this is a big deal at all, though it is still a fascinating technique that you may want to be aware of. Bear in mind, the snooper must be directly connected to a server using Intel’s Data Direct I/O (DDIO) technology. Also, to be clear, this is not a man-in-the-middle attack nor a cryptography crack: it is a cache-observing side-channel leak. And it may not work reliably at all on a busy system with lots of interactive data incoming.

How it works

DDIO gives peripherals, particularly network interfaces, the ability to write data directly into the host processor’s last-level cache, bypassing the system RAM. In practice, this lowers latency and speeds up the flow of information in and out of the box, and improves performance in applications, from web hosting to financial trading, where I/O could be a bottleneck.

Unfortunately, as boffins at VUSec – the systems and network security group at Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam in the Netherlands – have found, that leap into the CPU cache opens up the potential for side-channel holes. Earlier this year, the white-hat team uncovered and documented the aforementioned method in which a miscreant can abuse DDIO to observe other users on the network, and, after privately disclosing the flaw Intel, went public today with their findings.

DDIO is, for what it’s worth, enabled by default in all Intel server-grade Xeon processors since 2012.

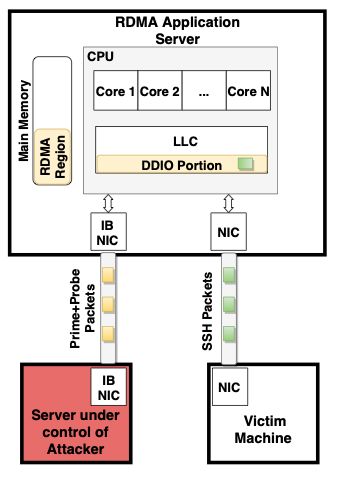

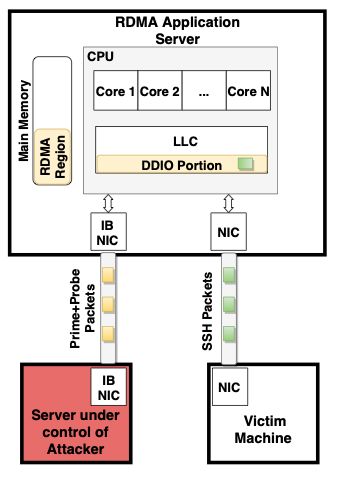

The technique, dubbed NetCAT, is summarized in the illustration below. This particular exploitation approach, similar to Throwhammer, requires the eavesdropper to have compromised a server that has a direct RDMA-based Infiniband network connection to the DDIO-enabled machine in use by the surveillance target. This would require the snooper to gain a strong foothold in the organization’s infrastructure.

Block diagram of the snooping technique … Credit: VUSec

Once connected, the spy repeatedly fills the processor’s last-level cache over the network, flooding the cache with its own data. The snoop observes any slight variations in the latency in its connection to detect when its data had been evicted to RAM by another network user, a technique known as prime+probe. A portion of this last-level cache is reserved for this direct IO use, thus the prime+probe method is not troubled by code and application data running through the CPU cores.

All this means the underlying hardware may inadvertently divulge sensitive or secret information. More technical details on NetCAT are due to be formally published in May next year.

“Cache attacks have been traditionally used to leak sensitive data on a local setting (e.g., from an attacker-controlled virtual machine to a victim virtual machine that share the CPU cache on a cloud platform),” explained the VUSec team, which was awarded a security bug bounty by Intel for its discovery.

“With NetCAT, we show this threat extends to untrusted clients over the network, which can now leak sensitive data such as keystrokes in a SSH session from remote servers with no local access.

“In an interactive SSH session, every time you press a key, network packets are being directly transmitted. As a result, every time a victim you type a character inside an encrypted SSH session on your console, NetCAT can leak the timing of the event by leaking the arrival time of the corresponding network packet.”

Armed with the timing of the packets, an attacker could potentially match intervals to specific keystrokes by comparing observed delays to a model of the target’s typing patterns.

The end result, as shown below, is a method for spying on SSH sessions in real time with nothing more than a shared server:

Youtube Video

If all of this sounds rather complex and unfeasible in real life, well, it is. The scenario VUSec laid out is mostly just a proof-of-concept rather than a likely attack scenario, as Intel pointed out in its statement to El Reg.

“Intel received notice of this research and determined it to be low severity (CVSS score of 2.6) primarily due to complexity, user interaction, and the uncommon level of access that would be required in scenarios where DDIO and RDMA are typically used,” a Chipzilla spokesperson said.

Deja-wooo-oooh! Intel chips running Windows potentially vulnerable to scary Spectre variant

READ MORE

“Additional mitigations include the use of software modules resistant to timing attacks, using constant-time style code. We thank the academic community for their ongoing research.”

As with most side-channel attacks, the process of actually exploiting the bug is rather tedious and unlikely, though it demonstrates a fundamental flaw that can be difficult, if not impossible, to address with anything short of a hardware redesign.

While VUSec agrees with Intel that adding software protections against timing attacks will make the spying harder to carry out, the only sure way to remove the vulnerability is to disable DDIO entirely, and lose the performance benefits.

“As long as the network card creates distinct patterns in the cache,” the VUSec team said, “NetCAT will be effective regardless of the software running on the remote server.” ®

Article source: http://go.theregister.com/feed/www.theregister.co.uk/2019/09/10/intel_netcat_side_channel_attack/

Check out

Check out

Check out

Check out

Check out

Check out  Check out

Check out