Who’s to blame for security problems? Surveys say, EVERYONE

Last week a cluster of surveys were released, showing some contrasting views of the main sources of IT security risk, and some revealing overlaps.

Last week a cluster of surveys were released, showing some contrasting views of the main sources of IT security risk, and some revealing overlaps.

The studies all asked professional IT workers what their main worry points were, and who they thought were the main causes of security incidents in their organisations.

The biggest study was conducted by forensics and risk management firm Stroz Friedberg. They covered businesses across the US, and found that most were pretty worried about cyber dangers.

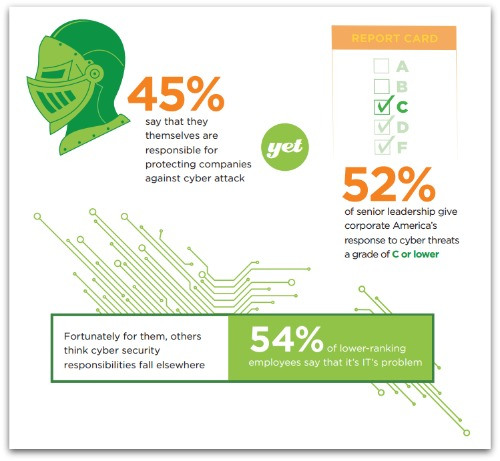

Their main highlight was the risky behaviour of senior management. 87% of top brass send work files to personal email or cloud accounts so they can work on them from home or the road, while 58% have sent sensitive data to the wrong person and more than half admit taking company files or data with them when leaving a post.

60% of those questioned gave their firm a “C” grade or worse when asked how well they were prepared to combat cyber threats.

Stroz Friedberg provide an executive summary of the survey’s findings, plus an infographic-style full report.

A second study, this time from Osterman Research and again speaking mainly to mid-sized businesses (averaging 10,000 users) across the US, also found high levels of anxiety about how people behave on their work computers.

Employees introducing malware into company networks was cited as a serious concern by more than half of respondents – 58% for web browsing and 56% for personal webmail use. 74% said their company networks had been penetrated by malware introduced via surfing, and 64% through email, in just the last 12 months.

Backing this up is another study conducted by SecureData, which found that 60% of those questioned thought the biggest risk to their firm’s security was simple employee carelessness.

It also found security matters were given a worryingly low priority in some organisations, with 44% saying the main responsibility for security decision-making rested on the shoulders of junior IT managers.

This all cycles back in to the Stroz Friedberg stats, in which around half of C-level management admitted they themselves should be taking more of a leading role in pushing for better security, while a similar level of lower-grade employees thought the responsibility really lay with specialist IT security staff rather than themselves or their corporate leaders.

As always with mass studies, the sample size is pretty important, and all of these are on the small side – 764 people were questioned for the Stroz Friedberg report, 157 for the Osterman study and just 110 for the SecureData survey.

The choice of questions is also a major factor in surveys, as answers can vary wildly with just a minor tweak in wording.

But despite these opportunities for inaccuracy and bias, these overlapping studies all seem to be coming to similar conclusions. We’re all very concerned about malware and other security risks, but for the most part we tend to hand off responsibility for avoiding them to others, and continue to indulge in risky behaviours ourselves.

People just aren’t getting the message and understanding how risky it can be to do personal stuff on our work systems, or to take sensitive work files home to our own, less well secured machines.

We’re not being cautious enough with our web browsing, email and social sharing, with phishing continuing to be a problem despite years of alerts and user education.

This is especially true with sensitive accounts some people have to use in their jobs – as the ongoing success of the Syrian Electronic Army in embarrassing the social media arms of large firms shows.

Even after multiple breaches all over the place, which you’d think would put most people in similar positions on their guard, it’s still possible to fool people into handing their login details over.

Even after multiple breaches all over the place, which you’d think would put most people in similar positions on their guard, it’s still possible to fool people into handing their login details over.

So perhaps it’s time to stop worrying about who’s the most to blame and who needs to take charge, and face up to the fact that IT security only works if we all do our bit.

We can’t rely on software or policies to combat our own stupidity, laziness or desires – we need to take some responsibility, pay some attention and put some more effort into making sure we’re not the weakest link.

Follow @VirusBtn

Follow @NakedSecurity

Image of people and mouse on mousetrap courtesy of Shutterstock.

Article source: http://feedproxy.google.com/~r/nakedsecurity/~3/yUdpgpzevbk/

There’s been much fiddling around with security warnings to see which versions work best: should they be passive and not require users to do anything? (Not so good.) Active? (Better.) Where should the dialogue boxes be positioned? What about the amount of text, message length or extent of technical gnarliness?

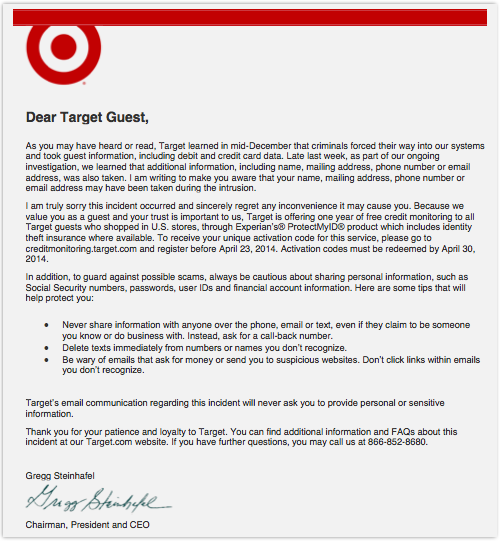

There’s been much fiddling around with security warnings to see which versions work best: should they be passive and not require users to do anything? (Not so good.) Active? (Better.) Where should the dialogue boxes be positioned? What about the amount of text, message length or extent of technical gnarliness?  A Naked Security reader just emailed us to say, “I received a message from Target about

A Naked Security reader just emailed us to say, “I received a message from Target about

Those are the guys who

Those are the guys who  In May 2013, retailer Nordstrom said that yes, it was

In May 2013, retailer Nordstrom said that yes, it was  Smartphones with WiFi turned on regularly broadcast their MAC address (a more-or-less unique device ID) as they search for WiFi networks to join. That address acts like a unique cookie that can be used to identify an individual over repeated visits. In an area with a few detectors in place it can also be used to determine a device’s location.

Smartphones with WiFi turned on regularly broadcast their MAC address (a more-or-less unique device ID) as they search for WiFi networks to join. That address acts like a unique cookie that can be used to identify an individual over repeated visits. In an area with a few detectors in place it can also be used to determine a device’s location. Apple is understandably proud of its App Store.

Apple is understandably proud of its App Store.

There’s been much fiddling around with security warnings to see which versions work best: should they be passive and not require users to do anything? (Not so good.) Active? (Better.) Where should the dialogue boxes be positioned? What about the amount of text, message length or extent of technical gnarliness?

There’s been much fiddling around with security warnings to see which versions work best: should they be passive and not require users to do anything? (Not so good.) Active? (Better.) Where should the dialogue boxes be positioned? What about the amount of text, message length or extent of technical gnarliness?  A Naked Security reader just emailed us to say, “I received a message from Target about

A Naked Security reader just emailed us to say, “I received a message from Target about

Those are the guys who

Those are the guys who