Yesterday, we wrote about the latest network security breach at Adobe.

Customer data was stolen, including login IDs, hashed passwords, encrypted credit card numbers and card expiry dates. (Adobe didn’t apply the adjective “encrypted” to those, so maybe they weren’t.)

But the breach wasn’t limited to customer records: some 40GB of Adobe source code was supposedly spirited away at the same time.

But the breach wasn’t limited to customer records: some 40GB of Adobe source code was supposedly spirited away at the same time.

Some of you expressed concerns about the effect that this source code theft might have on security, and suggested that we offer some opinions on what the risks might be.

Here you are.

Note. We’re not out to excuse Adobe’s breach here, nor to imply that code leaks of closed-source software are inconsequential. We’re just trying to help you see all sides of the picture. We hope you agree with our conclusions.

Which product sources were stolen?

According to Adobe, source for Cold Fusion and Cold Fusion Builder (used for creating websites), and for Acrobat (for creating portable documents) was almost certainly taken.

Other products may have been scooped up as well.

Will the stolen source code lead to lots of zero-day exploits?

This is a common fear – in fact, one of the researchers who came across the stolen code on the underweb went so far as to suggest that “this breach may have opened a gateway for a new generation of viruses, malware, and exploits.”

It’s true that source code usually means you don’t need to spend ages disassembling executable files to find out what they do, especially if you have fully-commented code and the original variable names.

You might even find notes from the programmers explaining complex or arcane parts of the code, or offering warnings of bugs that need fixing.

But researchers regularly find obscure and complex exploits against proprietary products without source code, while at the same time failing to spot long-standing vulnerabilities in products that are entirely open source.

So I don’t doubt that the crooks are pleased with their haul, but even if the source code makes their vulnerability research easier, it isn’t an automatic gateway to new exploits.

Remember that most vulnerabilities aren’t uncovered through manual analysis by humans, but through automated, deductive techniques such as fuzzing (running a program millions of times with successive inputs that change slightly each time until it crashes).

And working out how to exploit a vulnerability usually requires you to build up a detailed picture of what is going on inside the product’s executable code as it actually runs, whether you have the source code or not.

But if there *are* new zero-days found via the source, won’t it be the crooks that find them?

As a commenter on our earlier article pointed out:

Opening up the source code to uninvited criminals is very different from opening it up, as open source, to the public at large, so we now have the worst of all worlds. Obscurity of still-closed source code known only to the owners and a team of people intending to exploit it. That can’t be good.

Those are reasonable fears, since the only “new eyes” on the source are going to be those of criminals.

So, even if possessing the source bestows only a tiny advantage, that advantage won’t be used for good.

Do you think these “new eyes” will focus Adobe on reviewing its code promptly, and thus be a silver lining?

I think you can guess the answer to that question for yourself. (Perhaps it was rhetorical?)

And remember that although new eyes may well see something that has been overlooked before, “old eyes” have the twin advantages of familiarity and experience.

Will the source make it easier for the crooks to build Trojanised verions of Adobe products?

If the crooks have the necessary build environment and build tools, then they may be able to create their own official-looking versions of the software.

But large, proprietary software projects are notoriously difficult and time consuming to build, especially outside their usual development ecosystem, so this might not actually be the quickest and easiest way to produce Trojanised versions.

After all, the crooks have an easier way of getting official-looking versions already: just pirate the real thing.

Even if you build from source instead of patching an existing executable, you won’t be able to sign your new creation as a legitimate Adobe file without an Adobe code signing key.

And you’ll still have to persuade your victim to download and install your unofficial version.

But what if the crooks stole code signing keys along with the source code?

If so, they can make any program appear legitimate, even one without a single line of Adobe source code in it.

(This already happened to Adobe, about a year ago.)

What if the crooks got write access to the source while they were inside the network?

That might have allowed them to Trojanise Adobe’s own code repository by adding in a backdoor, a security hole, or any other sort of malware.

Then, when Adobe produced an official build and digitally signed it, the Trojan would be built-in from the start.

That would, indeed, be very bad.

But I’m sure that Adobe is already industriously conducting a stricter-than-usual audit of all recent changes to its codebase, which ought to allow it either to find and remove any unauthorised changes, or to conclude that no such changes were made.

Note that open source products, where there is often much less control over who can introduce or propose changes, and where the code is already a matter of public record, face the problem of maliciously-minded changes all the time.

Although there have been some occasional failures in the open source community, they are rare.

Sneaking unwanted changes past experienced code maintainers using modern change management tools is harder than you might think.

Why doesn’t Adobe just make its products open source and have the last laugh at the crooks?

Cute idea.

But you’d have to convince the Adobe shareholders that it wouldn’t affect the value of Adobe’s business.

Also, there are almost certainly parts of the codebase that couldn’t easily be open-sourced, for example because they were licensed from a third party.

What if Adobe opened up the code to selected resesrchers, and threw in some tempting bug bounties?

Cute idea, and a good way to get some carefully-chosen “new eyes” that aren’t crooks to scrutinise the code.

If you’re asking because you’d like to have a crack at Adobe’s source code yourself, then I suggest you go straight to Adobe with that question.

Adobe’s Chief Security Officer might a bit busy right now, but I’m sure he won’t mind you asking, as long as you are polite (as well as genuine and serious about getting involved).

The worst he can say is, “No.”

Was the NSA behind this attack?

Cute idea.

You’ll have to ask the US government.

The worst it can say is, “No.”

Article source: http://feedproxy.google.com/~r/nakedsecurity/~3/m5U7y7fCWD4/

To wrap-up the three part Sophos Security Chet Chat 118, Vanja Svajcer from SophosLabs Croatia joined me in Berlin to discuss the finer points of unwanted software for Android.

To wrap-up the three part Sophos Security Chet Chat 118, Vanja Svajcer from SophosLabs Croatia joined me in Berlin to discuss the finer points of unwanted software for Android. Thirteen alleged hackers labeling themselves with the Anonymous brand were indicted on Thursday on charges that they conspired to coordinate distributed denial of service (

Thirteen alleged hackers labeling themselves with the Anonymous brand were indicted on Thursday on charges that they conspired to coordinate distributed denial of service (

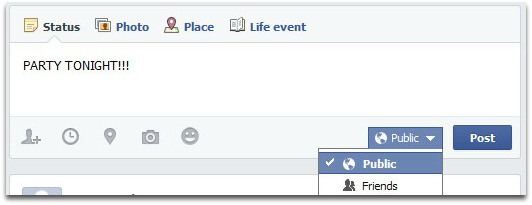

As it is, the public posting of a party on Facebook has left the Seales with a home that’s still a bit sticky, with the smell of vomit lingering days after the bacchanalia.

As it is, the public posting of a party on Facebook has left the Seales with a home that’s still a bit sticky, with the smell of vomit lingering days after the bacchanalia. To wrap-up the three part Sophos Security Chet Chat 118, Vanja Svajcer from SophosLabs Croatia joined me in Berlin to discuss the finer points of unwanted software for Android.

To wrap-up the three part Sophos Security Chet Chat 118, Vanja Svajcer from SophosLabs Croatia joined me in Berlin to discuss the finer points of unwanted software for Android. It’s Get Ready For Microsoft Patch Tuesday time again already, and

It’s Get Ready For Microsoft Patch Tuesday time again already, and  But the breach wasn’t limited to customer records: some 40GB of Adobe source code was supposedly

But the breach wasn’t limited to customer records: some 40GB of Adobe source code was supposedly  But the breach wasn’t limited to customer records: some 40GB of Adobe source code was supposedly

But the breach wasn’t limited to customer records: some 40GB of Adobe source code was supposedly