UK to trial national emergency alerts via mobile phones – what are the risks?

If you live in the UK and listened to the radio earlier this week, you might have heard Chester Wisniewski and me talking to a number of local radio stations about the UK government’s proposal to introduce an emergency alerting service based on mobile phone text messages.

If you live in the UK and listened to the radio earlier this week, you might have heard Chester Wisniewski and me talking to a number of local radio stations about the UK government’s proposal to introduce an emergency alerting service based on mobile phone text messages.

The plan, which will enter a trial stage later this month, is aimed at tapping into the ubiquity of mobile phones and the simplicity of Short Message Service (SMS) text messages to provide an effective method of giving clear and concise advice in the event of an emergency.

Radio and TV are highly effective tools that already get the news out rapidly in the event of local or national crises, but if you aren’t watching or listening at the moment that the alert goes out, you miss it.

Augmenting this with text messages may not be the most cutting-edge approach – texts are so 1999, after all – but it will work with just about every mobile phone in the UK, and just about everyone has a mobile phone.

It all sounds uncontroversial, doesn’t it?

You can probably imagine any number of local incidents that, were they to happen in your town, you wouldn’t mind hearing about without needing to be watching a TV or listening to a radio at the time.

At the risk of sounding a bit gruesome, examples might be: factory on fire, poisonous smoke billowing out; flood waters burst banks, CBD inundated; train accident, blood donations needed urgently; and so on.

But many, if not most, of the radio interviewers were at best cautiously optimistic, and with good reason: they wanted to speak to computer security experts because they wanted to consider the potential security risks before endorsing the proposal.

Thinking through the privacy implications before implementing a plan that is “obviously” the right thing to do?

That’s a good sign, if you ask me!

Quantifying the risks

So, how might this work, and what are the risks?

• Knowing whom to tell

You can build a giant list of users, and send them each an SMS in turn when you have something to say. This makes the service opt-in (unless you compel the mobile operators to hand over their subscriber databases), so the people who will receive the alerts are those who genuinely want them.

But it’s inefficient, since you have to send thousands or millions of messages, one by one, and for local emergencies, it doesn’t automatically target people on the spot (they might be out of town for the day, or have their phone turned off).

And there’s the problem of maintaining and disseminating the list so it can be used in real time: that list would be a prized possession for cybercrimimals.

And there’s the problem of maintaining and disseminating the list so it can be used in real time: that list would be a prized possession for cybercrimimals.

Or you can use SMS-CB, or “cell broadcasts,” where the mobile operator simultaneously sends a message to all the phones currently in a particular cellular area, thus promptly and efficiently reaching phones that are in range, and appropriately located.

But there’s no opt-in, and although many phones can opt out of CBs with a configuration setting, that’s usually an all-or-nothing approach.

• Authenticating the messages

Cybercriminals are adept at hijacking news stories, especially those involving tragedy and disaster, to peddle their own fraudulent information, or to spread misinformation and fear.

And they’re adept at copying the look and feel of genuine security warnings to give themselves an aura of legitimacy that misleads people, especially when they are in a hurry.

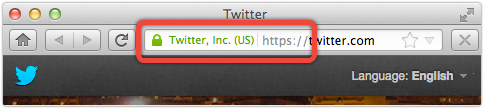

For web pages, there’s room in the browser’s interface for visual alerts that can’t easily be forged or disguised by the crooks (the HTTPS padlock in the address bar, for example), and those can help well-informed users to distiguish fake from real.

We don’t have similar protections for SMSes, and while the brevity of text messages is handy for clarity and simplicity in an emergency, it makes them easy to clone, or copy, or spoof, in a believable way.

• Tolerance for unexpected messages

Several of the interviwers noted that they suffer a similar problem to me: SMS fatigue.

We already receive so much SMS spam (what Naked Security jocularly calls SPASMS), urging us to consolidate our debts, or trying to sell us insurance we don’t need, that our tolerance for text messages is very low.

We’re probably the sort of people who wouldn’t opt in to any service, even a well-meant one, that required us to hand over our mobile phone details.

Unless we were expecting a message from a specific source (such as a two-factor authentication code we know is on the way), we wouldn’t pay much attention to it on the grounds that we never opted in to start with.

• Safeguarding the system

Similar emergency alerting systems, though admittedly not SMS-based ones, in other countries, have had terrible trouble with hackers.

Not because they were hacked frequently, but because they were hacked and abused at all – it only takes one fake emergency to cause panic, or to destroy trust for ever in the alerting system.

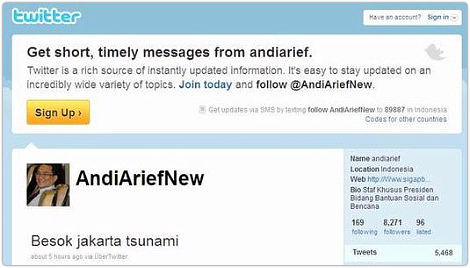

Indonesia’s disaster management adviser’s Twitter account was hacked; someone sent a bogus message claiming “Jakarta: tsunami arrives tomorrow.”

And in Montana, US, a TV-based alerting system was abused to send out warnings of a zombie apocalypse. (It might sound funny in hindsight, but it is a dire reminder of why security matters fourfold in alerting systems of this sort.)

Should it go ahead?

As one interviewer, desipte his own sceptical concern, pointed out, “The fact that there are lots of potential problems is no reason not to do it.”

He’s right.

What I applaud in this case is that the trials, which will involve up to 50,000 people, are to see if the system might work well enough in the UK to be adopted there.

In the post-9/11 security era, it seems that the trials of many security systems are more about seeing how to implement them, not to decide whether to do so.

And security systems put in place “because it’s obvious they’ll do good,” may end up having quite the opposite result.

Image of hand holding mobile phone courtesy of Shutterstock.

Article source: http://feedproxy.google.com/~r/nakedsecurity/~3/r6QBRzQi-BU/