We need to talk about email

Sometimes big security problems go unfixed for so long that they sort of disappear.

They can disappear without being fixed or mitigated. They can disappear without anyone forgetting they exist or forgetting that they’re serious. They can disappear just because they become normal.

Today the people of the world will exchange about 250 billion messages using a system that has been shockingly insecure for decades: email.

Many of those billions of messages will contain personal, private or even confidential information because most of the people sending them just don’t know how easy it is to read somebody else’s email.

Many of those billions of messages will contain personal, private or even confidential information because most of the people sending them just don’t know how easy it is to read somebody else’s email.

As security problems go, email insecurity may not be fashionable, it isn’t bleeding edge, and it doesn’t have a logo or a PR friendly name like Heartbleed or Cryptolocker.

But it’s no less important.

To understand why email is so insecure let’s take a look at how an email gets from A to B.

How email travels

Emails travel from their source to their destination through a network of computers joined together by cables or Wi-Fi signals.

The computers and other hardware on the network negotiate the best delivery route for your traffic, including your email, as it passes through.

Your email might go directly from your own email server to the recipient’s email server – for example in business-to-business messages – where it is treated very specifically as an email.

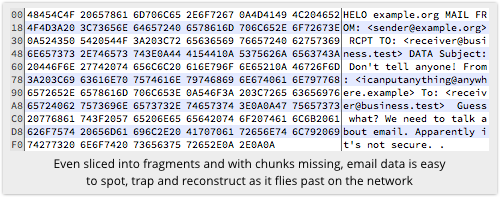

But the contents of the message (chopped into chunks the size of network packets) pass quietly through all the computers in the network chain.

Most of these computers aren’t mail servers, so they essentially ignore the message, or don’t bother to take special notice. At least, the ones that don’t have a packet sniffer on them ignore it. Probably.

Of course, even if a computer only gets to see your message flying past in fragments, it’s still easy to spot that it’s an email, because the fragments contain give-way signs.

These include Simple Mail Transfer Protocol (SMTP) commands like HELO sending.server.example and MAIL FROM: sender, as well as telltale email headers including content hints like Subject: Very Important! or information on the delivery path followed so far in the form of Received: from mail.gateway.example.

Additionally, as your email makes its way its way from email server to email server, it is logged and its contents stored in their entirety, at least temporarily, on each and every server it passes through.

In many cases, anyone who is a sysadmin on any of those servers will be able to examine, copy, delete, and perhaps even modify, your messages and the logs of their journey.

Of course, on the internet, the route an email takes from A to B can include hardware, cables and airspace operated, owned or pwned by any number of countries, organisations or individuals. Implicitly, email trusts them all.

At any point or points on its journey the email may be scanned to determine if its content resembles spam or contains malware.

Its contents may also quite deliberately be read and interpreted (even without the sender’s consent) to determine what kinds of advertising the recipient is most likely to respond to.

Put another way: an email is like a postcard that’s delivered by passing it from hand to hand through a crowd of strangers.

Given its very public and overly trusting means of delivery it should be pretty clear that there’s really only one sensible way to keep an email secret: to put it in a container with a padlock that only the recipient can unlock (or, in computing terms, to encrypt it in a way that only the recipient can decrypt).

So, of course, that isn’t how we do it.

The best way to secure email

Like a lot of the early network protocols, SMTP was conceived without any thought of security at all.

Early network protocols like Telnet, File Transfer Protocol (FTP), the Domain Name System (DNS) and SMTP were ground-breaking technologies that transformed computing.

They were born into trustworthy environments and raised by trustworthy folk who simply couldn’t imagine what obstacles and villainy their work would face in the decades that followed.

First we built the internet and then, only after we understood the nature of what we’d made, did we begin to secure it retrospectively.

That process is still going on and for the first generation of internet technology security has either been too much altogether or a difficult, better-late-than-never bolt-on.

Adding a layer of security to a system that’s as deeply entrenched as email is no small matter.

Adding a layer of security to a system that’s as deeply entrenched as email is no small matter.

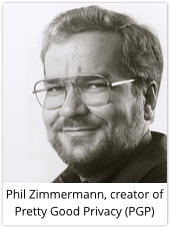

However the means to secure emails properly has been available, thanks to Phil Zimmermann and his creation PGP, completely free of charge for at least 23 years.

PGP and the OpenPGP standard that followed delivered end-to-end encryption: the ability for a user to encrypt an email in way that only the recipient can untangle.

Unfortunately almost nobody uses it.

The chances are that you already use an email client that supports PGP encryption but still send unencrypted mail.

There are many reasons that end-to-end encryption isn’t used: people don’t know it exists; they don’t know why they need it; it’s optional; it can be difficult to understand; it can be difficult to set up; and it doesn’t deliver an immediate and satisfying reward.

Worse still, the recipient has to be willing to join in too, or they won’t be able to read your messages.

Whatever the reasons, the fact is that leaving it for users to bolt proper security onto an email system they’re happy with simply hasn’t delivered the goods.

Which is what led us to the second best solution.

The second best way to secure email

The second best option for email security, and the only option that is actually used on any kind of meaningful scale, is to encrypt the communications between the servers in the delivery chain using TLS (Transport Layer Security).

The emails can’t be intercepted when they’re travelling between servers, but that’s it.

They aren’t encrypted before they leave your computer, or while they’re being processed by the email servers that pass them along, or after they reach their final server.

An email delivered over TLS still implicitly trusts every server it passes through, as well as the network at each end, used by you to create the email and have it queued for delivery and by the recipient to retrieve it and read it.

Nevertheless, TLS keeps the content of messages secure in transit, and has two main factors in its favour over end-to-end encryption: it can be rolled out by changing far fewer computers (only mail servers need reconfiguring), and setting it up is more often in the hands of experts than end users.

Sadly, any two servers in the delivery path of your emails will only put up an encrypted “tunnel” for your message if both sides know how, and agree to bother.

That happens far less often than you’d hope.

According to its transparency report, Gmail (which only rolled out 100% encryption between its own servers in March 2014) skips encryption on 25% of outgoing connections and 43% of incoming connections.

In other words, Gmail stands ready to create TLS tunnels to secure your email packets in transit, but between one half and one quarter of their nearest neighbours in the delivery chain can’t.

Or don’t bother.

That means if you want to do the right thing yourself, and use TLS to guarantee that email is encrypted into and out of your organisation, you have to reject all email from non-TLS senders, and outright refuse to deliver it to non-TLS receivers.

If Gmail’s measurements are anything to go by, you can then expect a quarter of your sales proposals not to go out at all, and nearly half of your incoming orders to be lost.

Good luck with that.

Is anything going to change?

Maybe.

Since Edward Snowden revealed that the NSA has been siphoning off vast troves of internet data (including massive amounts of email), encryption and encryption technologies have been given a new lease of life.

The major online service companies have all started issuing transparency reports, encrypting the connections between their data centres and encrypting the connections between web browsers and their webmail products.

Most significantly Google, which seems to have caught the encryption bug most visibly of all, recently announced End-to-End, a Chrome browser plugin that aims to make it easier to use OpenPGP.

You remember OpenPGP – that’s the way we should be encrypting email.

It isn’t ready yet, but if you’re technically savvy enough to compile your own plugin from source you can start testing it today.

The project is significant for two reasons: firstly because it aims to ameliorate the most serious problem with end-to-end email encryption, and secondly because it’s open source.

Being open source means that other people can review it, change it, include it in their own products or create their own variations of it.

It might start life as a browser plugin for Chrome but if it works and people like it then it will spread to other browsers and other platforms.

The first such contagion has already occurred with Yahoo’s recent announcement that it plans to bootstrap its own PGP plugin using Google’s.

In the meantime, the roll out of TLS will continue and of course you don’t have to wait for Google or Yahoo to deliver their plugins to benefit from OpenPGP – they’re just making something that already exists easier to use.

Yahoo’s OpenPGP product will be ready in 2015, some 44 years after Ray Tomlinson sent the first email over a network.

The chances are that when it reaches its half-century email still won’t be completely secure, but that still won’t be a reason not to talk about it.

Follow @MarkStockley

Follow @NakedSecurity

Images of post courtesy of Shutterstock.

Article source: http://feedproxy.google.com/~r/nakedsecurity/~3/wnBgEx8H0aU/