Where have all the Bitcoins gone?

In the past, when we’ve covered anything that sounded even remotely like “Bitcoin trouble,” we’ve ended up with well-meaning Bitcoin fans on our case.

In the past, when we’ve covered anything that sounded even remotely like “Bitcoin trouble,” we’ve ended up with well-meaning Bitcoin fans on our case.

That’s because many of, though not all, the Bitcoin troubles we have written about have really been troubles at the interface between Bitcoins and traditional currency.

That interface is made up of the exchanges that let you trade regular money into and out of Bitcoinage.

Examples include:

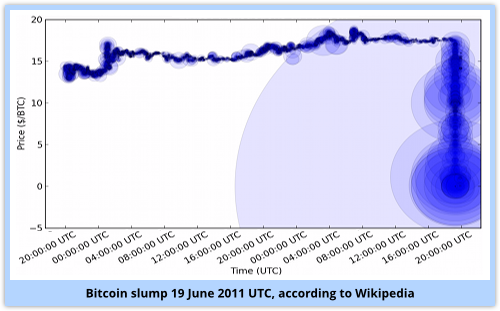

June 2011. Stolen passwords were used for fraudulent trades at Mt Gox, dumping the price from $15 to $0.01 (one US cent) in about an hour.

May 2012. An exchange called Bitcoinica allegedly had $225,000 stolen, followed by another $90,000 later the same year.

September 2012. $250,000 was stolen from boutique exchange Bitfloor after an encryption lapse during a server upgrade.

March 2013. A 25% value drop was precipitated by incompatibility between successive Bitcoin software versions, causing legitimate transactions to be rejected.

May 2013. Online gaming company ESEA illegally snuck Bitcoin mining code into its software – ironically in its anti-cheating module.

August 2013. A flaw in the Java pseudorandom number generator allegedly led to Bitcoin thefts from improperly-secured digital wallets on the Android platform.

November 2013. Small exchanges in Australia, China and Denmark “vanished along with the money” after claiming they’d heen hacked.

As we remarked in November last year:

[M]any Bitcoiners seem to be big on risk, entrusting their precious Bitcoin assets to a wide range of online wallet services, where they are firmly in the sights of cybercrooks…Remember, you don’t have to keep your Bitcoins online with someone else: you can store your Bitcoins yourself, encrypted and offline.

There was life before cloud storage, and there will be life after it.

How prescient those words seem now!

It’s been tricky enough for old-school retailers to keep things shipshape recently, with massive in-store breaches at companies like Target and Neiman Marcus.

These breaches occurred, at least in part, because most if not all of the companies’ cash registers fell under the remote control of malware-wielding cybercrooks.

Now add an unregulated currency like Bitcoin into the mix – one that has no physical form and doesn’t officially exist, yet has been deemed to be worth more than $1000 per “coin” at times in the past year – and things get trickier still.

As an anonymous correspondent wryly, if somewhat imprecisely, put it in an email I received recently, “…Because something uses funky cryptography and has become a techie daahling doesn’t mean that the ecosystem it spawns is imbued with the same Magic CryptoDust…“

We’ve had a blast of reminders of the truth of this throwaway remark lately, from the small, medium and extremely large parts of the Bitcoin world:

• Curiously-named Poloniex lost $50,000 due to a coding error (known as a race condition) in its Bitcoin withdrawal database.

If seems that you posted lots of withdrawals at the same time, and each one on its own would not have put you into the red, then the system would queue them all up and process the lot.

Only when the dust settled would Poloniex realise it had paid out your last few dollars over and over again.

• Flexcoin closed down earlier this week after hackers processed a fraudulent transfer of $600,000.

Reports suggest that’s everything that Flexcoin had on deposit, gone in one go.

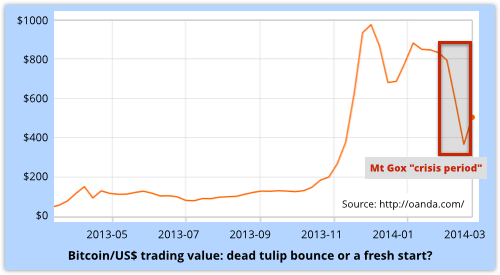

• Mt Gox, once the biggest Bitcoin exchange, closed up, filed for bankruptcy and declared that it was missing Bitcoins worth some $500,000,000.

You read that correctly: about half-a-billion dollars.

To be fair to Bitcoin fans, many of these problems have had little to do with the Bitcoin cryptographic infrastructure.

Bitcoin’s design didn’t cause Poloniex’s race condition, nor Bitfloor’s security lapse, nor Flexcoin’s suddenly-vanishing $600,000 of online currency.

Nevertheless, Bitcoin’s cryptography isn’t perfect.

Transactions, which have a one-off ID, are cryptographically hashed to mark them uniquely, but this hash is improperly computed.

Hash collisions, where two different IDs end up hashing the same, can’t be manufactured, but what you might call “anti-collisions” can.

The same ID can end up with two different hashes – one transaction being real, and the other being fake.

The Bitcoin community, in a rather splendid euphemism, calls this transaction malleability, but you can call it a cryptographic flaw.

Crooked transactors can use a deliberately created duplicate-yet-different transaction to trick naive exchanges into thinking that something has gone wrong, and demand a refund. (Smart exchanges use additional checks to help repudiate bogus transaction repudiations.)

And “anti-collisions” can be used to create Denial-of-Service (DoS) delays by peppering exchanges with bogus transactions that eat up time to cross-check and reject.

With all of this going on, will Bitcoin survive?

Recent trading values suggest it will, though you can expect traditional financial regulators and anti-money-laundering investigators to have some very keen questions right now.

Such as, “Where is that $500,000,000 Bitcoin stash from Mt Gox?”

Article source: http://feedproxy.google.com/~r/nakedsecurity/~3/qmMdee7xf3o/