Facebook is losing the fight against the spread of fake news

Leaked photos showing how Obama practiced Islam in the White House! Trump’s legalization of bald-eagle hunting! … The president’s cancellation of Saturday Night Live!!!

What do they have in common?

They’re all fake news, they’ve all been debunked, and yet you can still find those “news” articles on Facebook.

We already know that since the 2016 US presidential election, Facebook and other social media platforms have been in hot water over fake news.

Now, thanks to a report from the Guardian, we also know that in spite of Facebook’s new fact-checking system; its partnering with third-party fact-checkers including Snopes, ABC News, Politifact, FactCheck and the Associated Press; and its new “disputed” tag, which is supposed to be slapped on to dodgy news stories but isn’t always, those fake stories are doing just fine, thank you very much.

Take ABC News, one of Facebook’s fact-checking partners. It’s got a dozen debunked stories on its “Fact or Fake” site. But you can still find versions of half of those bogus articles, strutting their stuff on Facebook without the “disputed” tag.

For example, here’s one about Obama’s supposed treasonous coup against Trump that’s still floating around:

Besides the Obama coup one, there’s a story claiming Obama is building a statue of himself for the White House, an article alleging that Republicans taking secret payments from Hillary Clinton, and others.

Not only are debunked articles not getting tagged, but there’s a consequence of the war against fake news that, in hindsight, we should have anticipated: traffic to some articles flagged as fake has skyrocketed as a backlash to what some groups see as an attempt to bury the “truth”.

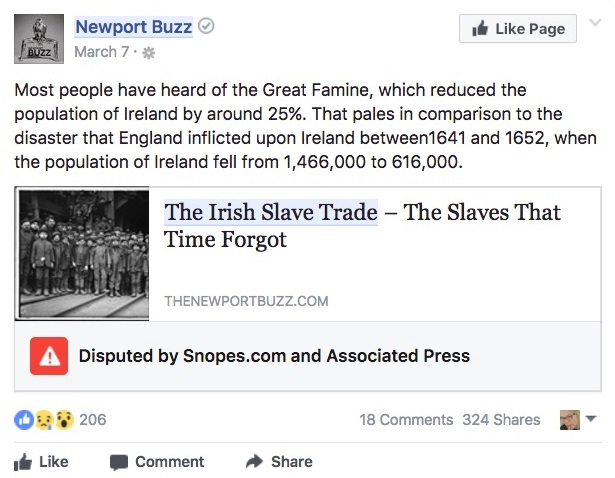

That’s what happened with a Newport Buzz article about the “Irish slave trade” having been “forgotten by time,” overshadowed by the African slave trade. The article falsely claimed that hundreds of thousands of Irish people were brought to the US as slaves. Facebook flagged it as possible fake news, and that’s when it went viral.

The Guardian quotes Christian Winthrop, editor of the local Rhode Island website that published the story:

A bunch of conservative groups grabbed this and said, ‘Hey, they are trying to silence this blog – share, share share!’ With Facebook trying to throttle it and say, ‘Don’t share it,’ it actually had the opposite effect.

Some of the press partners working on debunking fake news say that it’s tough to tell if Facebook’s new system and its “disputed” tag are having any effect. Brooke Binkowski, the managing editor of Snopes, told the Guardian that fake news is still “flying thick and fast”.

Without data, it’s tough to get a handle on whether anything is changing, they say. Facebook has declined to share the type of data that could help, such as how many articles have been flagged, how the flag impacts traffic and engagement, whether there are specific websites most frequently cited, and how long after publication the flags are typically added.

Facebook told the Guardian that the company has “seen that a disputed flag does lead to a decrease in traffic and shares”, but declined to elaborate.

Some of the sites that publish fake news say that they’ve seen a drop in traffic since Facebook started to rely on outside fact-checkers, but they haven’t handed over much detail on the supposedly reduced traffic.

Jestin Coler, a writer who got widespread attention for the fake news he published last year, noted that Facebook’s trying to swim upstream, having to fight the rush of fake news that goes viral way before Facebook systems, partners or users have a chance to report it.

These stories are like flash grenades. They go off and explode for a day. If you’re three days late on a fact check, you already missed the boat.

Coler’s no longer in the fake-news business. But it wasn’t any move by Facebook that pushed him out. Nor was it due to fake news being less than lucrative: he told NPR that stories about other fake-news makers pulling in between $10,000 and $30,000 a month apply to him.

Rather, he got out of the fakery business because of his conscience, he told NPR.

But with that kind of money on the table, you have to wonder: does Facebook really want to stop fake news?

Likely not, said Melissa Zimdars, assistant professor of communication and media at Merrimack College. Zimdars created a list of untrustworthy news sites that went viral. She told the Guardian that she thinks that Facebook’s just trying to squirm out from under bad press with all its anti-fake-news efforts:

My initial read on it is it’s ultimately kind of a PR move. It’s cheap to do. It’s easy. It doesn’t actually require them to do anything.

Facebook, for its part, says the “disputed” tags are just one tool in its kit. Here’s what Facebook told the Guardian:

We take seriously the issue of fighting false news and are utilizing an all-of-the-above approach. There’s no silver bullet solution, which is why we’ve deployed a diverse, concerted and strategic plan.

Follow @NakedSecurity

Follow @LisaVaas

Article source: http://feedproxy.google.com/~r/nakedsecurity/~3/Ex4gzlCeHMU/