This week’s super-scary security topic is deanonymisation.

The media excitement was kindled after the BBC wrote up a short article about an intriguing paper entitled Dark Data, presented at the recent DEF CON conference in Las Vegas.

We weren’t at DEF CON, so we hoped that the many stories written about this fascinating paper would tell us something useful about what the researchers did, and what we could learn from that…

…but we were quickly disappointed, faced with little more the same brief story over and over again, told in the same brief way.

So we decided to dig into the matter ourselves, and soon found that the Dark Data paper was the English language version of a talk the researchers presented in German last year at the 33rd Chaos Computer Club conference in Hamburg.

We were delighted to find that the German talk had an title that was itself in English, yet even cooler than the DEF CON version: Build your own NSA.

If you have the time, the video makes for interesting viewing. There are simultaneous translations of satisfactory quality into English and French if your German isn’t up to scratch. If you follow along in the DEF CON slide deck hen you will have an accurate English version of the visual materials.

Digital breadcrumbs

Very greatly simplified, here is what the researchers did to collect their data, and what they were able to do with it afterwards.

First, they set up a bogus marketing consultancy – a cheery, hip-looking company based in the hipster city of Tel Aviv.

Second, they used the online “marketing grapevine” to look for web analytics companies that claimed to provide what’s known as clickstream data.

Clickstreams keep a log of the websites that you visit, the order you visit them, and precise URL details of where you went on each site each time you visited. If all you are interested in is how your own customers behave when they’re on your site, this sort of data seems innocent enough. Indeed, clickstreams are often referred to by the vague name of browsing metadata, as though there’s nothing important in there that could stand your privacy on its head.

Third, the researchers soon wangled a free web analytics trial, giving them near-real-time access to the web clickstreams of about 3,000,000 Germans for a month.

In theory, this clickstream data was supposed to be harmless, given that it had been anonymised. (That means real names were stripped out and replaced with some kind of meaningless identifier instead, for example by replacing Paul Ducklin with the randomly-generated text string 4VDP0QOI2KJAQGB.)

At least, that’s what the web analytics company claimed – but their anonymised data turned out to be a privacy-sapping gold mine.

Anonymisation and deanonymisation

We’ve written before in some detail about how anonymous data often isn’t anonymous at all, and why.

So you probably aren’t surprised to hear that in this case, too, the anonymisation could sometimes very easily be reversed.

Part of the problem – if you ignore whether it should be lawful to collect and monetise clickstream data at all – is that marketing companies love detail, and web analytics companies are correspondingly delighted to provide it.

It’s not enough to know that someone is visiting your website – you’re also supposed to take careful notice of how they behave after they arrive, to help you answer questions about how well your site is working.

Once they’ve done a search, do they stick around, or get frustrated and leave? If they look at jeans, do they think of buying sneakers at the same time? Do Californians spend longer on the site than New Yorkers?

The theory is that if you don’t pass on data that details precisely who did what, but merely how people behave in general, then you aren’t treading on anyone’s privacy if you sell (or buy) clickstream data of this sort.

Sure, you know that user T588Z1CN4CC6XW8G visited the recipe pages 37 times in the month, while 61XLRW0NOW3G644 browsed to 29 products but didn’t buy any of them.

But you don’t know who those randomly-named users actually are – so, what harm is done, provided that you don’t also get a list that maps the random identifiers back to usernames?

Sadly, however, the URLs in your browsing history are surprisingly revealing, and the Dark Data researchers were able to figure out 3% of the users (100,000 out of 3,000,000) directly from clues in the URLs.

For example, if you login to Twitter and go to the analytics page, the URL looks like this:

https://analytics.twitter.com/user/[TWITTERHANDLE]/tweets

So if the clickstream data looks like this…

usr=PI38H1H7JGX2HZH utc=2017-08-01T13:00Z uri=https://analytics.twitter.com/user/[TWITTERHANDLE]/tweets

…then you know who PI38H1H7JGX2HZH is right away, without doing any more detective work at all.

Public versus private

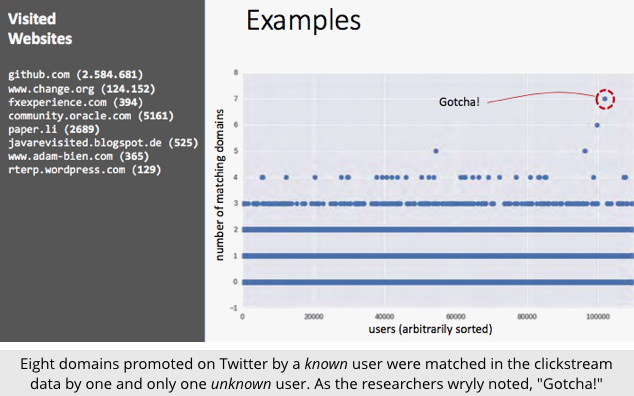

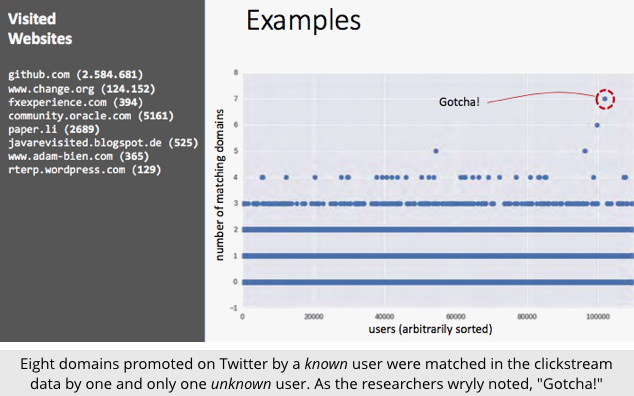

The researchers also showed how you can often deanonymise individuals simply by comparing their publicly-declared interests with the data in the clickstream.

For example, if I examine your recent tweets, I’ll be able to extract a list of all the websites that you have recommended publicly, say in the last month. (The researchers automated this prcoecss using Twitter’s programming interface.)

Let’s say you told your Twitter followers that the following websites were cool:

github.com

www.change.org

fxexperience.com

community.oracle.com

paper.li

javarevisited.blogspot.de

www-adam-bien.com

rterp.wordpress.com

It’s reasonable to assume that you browsed to all of those sites yourself before recommending them, so they’ll all show up in your clickstream.

The burning question, of course, is how many other people visited that same collection of sites. (It doesn’t matter if they visited loads of other sites as well – just that they visited at least those sites, like you did.)

The researchers found that fewer than ten different domains was almost certainly enough to pin you down.

Millions of other people have probably have visited two or three of your favourite sites.

Only a few will have five or six sites in common with your list.

But unless you’re a celebrity of some sort, you’re probably the only person who visited all of your own favourite sites recently, and that’s that for your anonymity.

Getting at the details

If you’ve read this far, you are almost certainly wondering, “Where does such detail in the clickstream come from?”

Can cookie-setting JavaScript embedded in the web pages you visit explain all of this detail, for example?

Fortunately, it can’t: the researchers found that browser plugins were a significant part of the deanonymisation problem, which is something of a relief.

After all, the owner of a website decides, at the server end, whether to add JavaScript; on the other hand, but you get to decide, in your own browser, which plugins to allow.

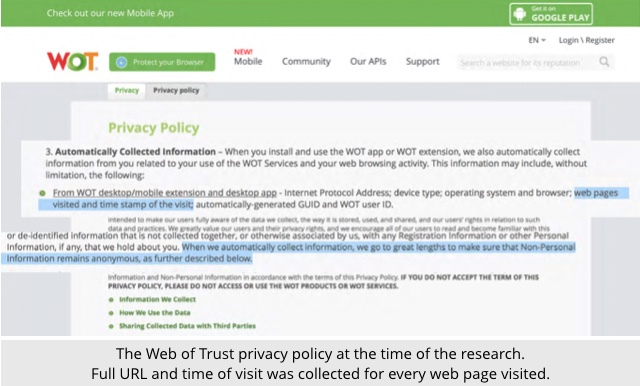

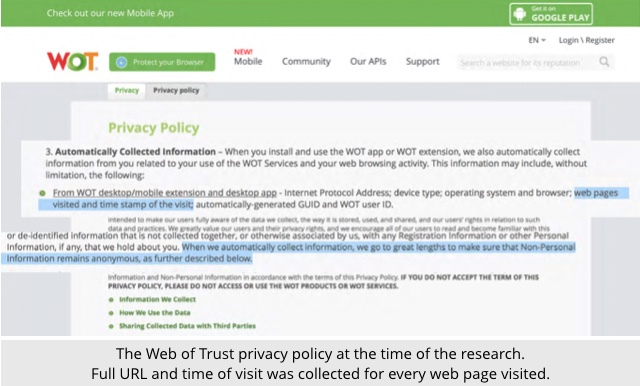

Browser plugins are a security risk because a malicious, careless or unscrupulous plugin gets to see every link you click, as soon as you click it, and can leak or sell that data to a clickstream aggregator, who can sell it on.

And seems that plenty of web plugins fall into one of those categories, because the researchers suggested that 95% of the data in the clickstream they “purchased” in their free trial was generated up by just 10 different popular web plugins.

The researchers were able to verify whether a plugin leaked data directly into the clickstream simply by experimentation: install a plugin, visit a recognisable pattern of websites with the plugin turned on, then turn it off, then on again, and so on. If the traffic pattern shows up in the clickstream whenever the plugin is on, but not when it is off, it’s a fair assumption that the plugin is directly responsible for feeding the clickstream with URL data.

For what it’s worth, the researchers claim that the worst of the data-leaking plugins – this work was done a year ago, in August 2016 – was a product called WOT, ironically short for Web Of Trust, a plugin that advertises itself as “protect[ing] you while you browse, warning you against dangerous sites that host malware, phishing, and more.”

What to do?

Here are some things you can do to reduce your trail of digital crumbs, or at least to make them a bit less telling:

- Get rid of browser plugins you don’t need. Some plugins genuinely help with security, for example by blocking ads, limiting tracking behaviour, and restricting the power of JavaScript in web pages you visit. But even so-called “security add-ons” – as in the WOT case – can end up reducing your security. If in doubt, take advice from someone you know and trust.

- Use private browsing whenever you can. Browser cookies that are shared between browser tabs allow advertisers to set a cookie via a script embedded in one website and to read it back from another website. Private browsing, also known as incognito mode, keeps the data in each web tab separate.

- Clear cookies and web data automatically on exit. This doesn’t stop you being tracked or hacked, but it does make you more of a moving target because you regularly get new tracking cookies sent to your browser, instead of showing up as the same person for weeks or months.

- Logout from web sites when you aren’t using them. It’s handy to be logged in to sites such as Facebook and Twitter all the time, but that also makes it much easier to like, share, upload or reveal data by mistake.

- Learn where the privacy and security settings are for all the browsers and apps you use. Clearing cookies and web data from Safari on your iPhone is completely different to doing it in Firefox on Windows. Logging out of Facebook from the mobile app is different to logging out via your browser. Learn how to do it all ways up.

- Avoid sites that use HTTP instead of HTTPS, even if you don’t need to log in. When you visit an HTTP web page, anyone else on the network around you can sniff out the entire URL you just browsed to. On HTTPS pages, the domain names are revealed by your network lookups (so a crook can see that you just asked where to find nakedsecurity.sophos.com) but the full URLs are encrypted (so the crook can’t tell which pages you looked at or what you did there).

- Use an anonymising browser like Tor when you can. Tor doesn’t automatically make your browsing anonymous – if you login to Facebook over Tor, for example, you still have to tell Facebook who you are. But it makes it look as though you are coming from a different city in a different country every time, which makes you harder to keep track of or to stereotype.

You might be thinking that we missed an easy tip here.

It feels as though one “obvious” solution to improving your anonymity online is to do a bunch of extra browsing, perhaps even using automated tools, thus deliberately bloating your clickstream with content that doesn’t relate to you at all, hopefully throwing deanonymisation tools off the scent.

As the researchers point out in their video, however, that doesn’t work.

For example, the trick of tracking you back via the sites that you recently recommended on Twitter depends on whether anyone else visited those sites – not on whether you visited a load of other sites as well.

When it comes to generating, collecting and using clickstream data safely, less is definitely better than more…

…and none is best of all!

Article source: http://feedproxy.google.com/~r/nakedsecurity/~3/bW2rAO8wWKY/