For better machine-based malware analysis, add a slice of LIME

When built right, deep learning models are hugely effective malware and malicious web page detectors.

But there’s a problem: they almost never provide useful information about why they think a particular web page or application is rotten. They just spit out one number that basically says how likely the model thinks the sample is to be malicious. It’s a “black box” where the sample goes in, magic happens, and a classification comes out.

It’s all well and good for security shops that need to spot and stop danger in a hurry without having to think much about it. But if you’re a security researcher, you need to answer the why question to build better defenses down the road.

The good news is that tools to get there exist. At BSidesLV on Tuesday, Sophos principal data scientist Richard Harang focused one of them – Local Interpretable Model-Agnostic Explanations (LIME).

LIME was developed by researchers Marco Tulio Ribeiro, Sameer Singh and Carlos Guestrin at the University of Washington as a technique to explain how deep learning models make decisions about what’s safe or sinister.

The machine learning movement

A lot of security experts tout machine learning as the next step in anti-malware technology. Indeed, Sophos’ acquisition of Invincea earlier this year was designed to bring machine learning into the fold.

Machine learning is considered a more efficient way to stop malware in its tracks before it becomes a problem for the end user. Some of the high points:

- Deep learning neural network models lead to better detection and lower false positives.

- It roots out code that shares common characteristics with known malware, but whose similarities often escape human analysis.

- Behavioral-based detections provide extensive coverage of the tactics and techniques employed by advanced adversaries.

The ‘why’ problem

As great as that sounds, no technology is perfect. When it comes to machine learning, data scientists want a better explanation of why something is labeled malicious. Harang said:

The generic black-box nature of these classifiers makes it difficult to evaluate their results, diagnose model failures, or effectively incorporate existing knowledge into them. A single numerical output – either a binary label or a maliciousness’ score – for some artifact doesn’t offer any insight as to what might be malicious about that artifact, or offer any starting point for further analysis.

This is a problem, he said, because:

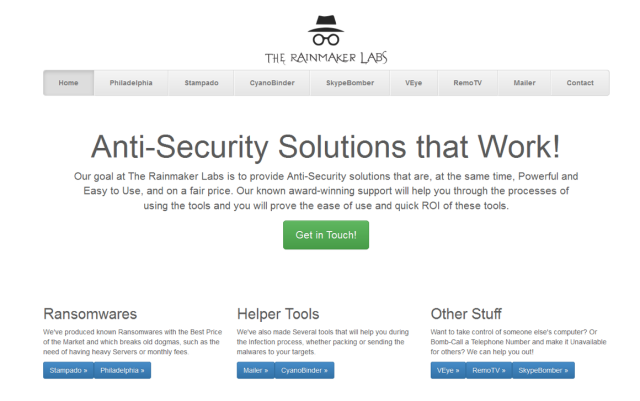

- If you’re an analyst whose job it is to say, “well, we can tell this executable is an example of ransomware because of X, Y, and Z,” deep learning models really don’t help you do your job, since all you can do is say “it’s probably malicious” without any sort of supporting evidence.

- Without supporting evidence, it’s hard to troubleshoot a deep learning model. If it suddenly starts giving us bad answers on some samples, it can be very hard to figure out why it’s doing it and how to fix it.

Enter LIME

In his talk, Harang explained how LIME can be adapted to take the analysis a step further than simply identifying features of the document that are critical to performance of the model (as in the original work). Analysts can also use it to identify key components of the document that the model “thinks” are likely to contain malicious elements.

By making some modifications to the LIME technique, researchers can figure out what kinds of patterns a model has extracted from the data, which can help improve the overall model, troubleshoot any mistakes it makes, and maybe even find and fix mistakes before they happen, Harang said.

LIME has what’s called Human Interperable features (HIFs). Each class of HIFs acts as a kind of lens through which researchers can analyze a file, allowing them to examine how specific features, such as scripts, hyperlinks, or even just particular pieces of the file might impact its classification.

Other points:

- Given 120kb of HTML document, LIME can narrow it down to the salient bits quickly and efficiently.

- Even when documents are not classified by the model as malicious, you can often identify key elements that look suspicious.

- By looking at different HIFs and their success in analyzing a document, you can examine what kinds of features the model has learned from the data.

- By moving HIFs to another sample and looking at their impact, you can evaluate the contextual sensitivity of features.

As Harang noted in his slides, “complex models are complex”. This makes it hard – but not impossible – to extract the right insight.

LIME is a good, general-purpose tool to do it. With some tweaks, LIME can turn a deep learning model into a useful tool for analysis of artifacts, highlighting potential sections of interest, he said.

By applying LIME across a range of documents and HIFs, he added, one can better understand the strengths and weaknesses of a model and biases in data, and use that fresh knowledge to make your deep learning model more effective going forward.

Follow @NakedSecurity

Follow @BillBrenner70

Article source: http://feedproxy.google.com/~r/nakedsecurity/~3/Uf4lndlG5oA/