Apple fixes that “1 character to crash your Mac and iPhone” bug

Apple has pushed out an emergency update for all its operating systems and devices, including TVs, watches, tablets, phones and Macs.

The fix patches a widely-publicised vulnerabiity known officially as CVE-2018-4124, and unofficially as “one character to crash your iPhone”, or “the Telugu bug”.

Telugu is a widely-spoken Indian language with a writing style that is good news for humans, but surprisingly tricky for computers.

This font-rendering complexity seems to have been too much for iOS and macOS, which could be brought to their knees trying to process a Telugu character formed by combining four elements of the Telugu writing system.

In English, individual sounds or syllables are represented by a variable number of letters strung together one after the other, as in the word expeditious.

That’s hard for learners to master, because written words in English don’t divide themselves visually into pronunciation units, and don’t provide any hints as to how the spoken word actually sounds. (You just have to know, somehow, that in this word, –ti– comes out as shh and not as tea.)

But computers can store and reproduce English words really easily, because there are only 26 symbols (if you ignore lower-case letters, the hyphen and that annoying little dingleberry thing called the apostrophe that our written language could so easily do without).

Better yet for computers, English letters always look the same, no matter what other letters they come up against.

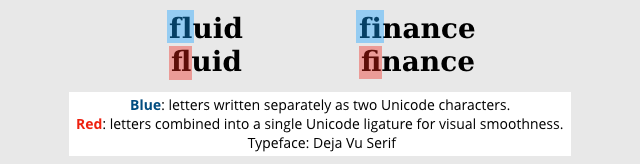

We do have some special characters in English typography – so-called ligatures that combine letters that are considered to look ugly or confusing when they turn up next to each other:

These English ligatures aren’t taught in primary school when you learn your alphabet, so you can go through your life as a fluent, native, literate English speaker and not even realise that such niceties exist. It’s never incorrect to write an f followed by an l, and little more than visual politeness to join them together into an fl combo-character.

Additionally, in English, we sometimes pronounce –e– as if it were –a– (typically in geographical names where the old pronunciation has lingered on, as in the River Cherwell in Oxfordshire, which is correctly said aloud as char-well); sometimes as a short –eh-,sometimes as a long –ay-, and sometimes as if it were several Es cartoonishly in a row, –eee-.

But many languages use a written form in which each character is made up of a combination of components that denote how to pronounce it, typically starting with a basic sound and indicating the various modifications that should be applied to it.

So each written character can convey an array of information about what you are looking at: aspirated or not (i.e. with an –h– sound in it), long vowel or short, sounds like –eee– rather than –ay-, and so on.

That’s great when you are reading aloud, but not so great when you’re a computer trying to combine a string of Unicode code points into a visual representation of a character for display.

It’s particularly tricky when you are scrolling through text.

In English, each left-arrow or right-arrow simply moves you one character along in the current line, and one byte along in the current ASCII string, but what if there are four different sub-characters stored in memory to represent the next character that’s displayed?

What if you somehow end up in the middle of a character?

Or what if you split apart a bunch of character components incorrectly, accidentally turning hero into ear hole or this into tat?

For that reason, unusual (or perhaps merely unexpected) combinations of characters sometimes cause much more programmatic trouble that you’d expect, as when six ill-chosen characters brought Apple apps down, back in 2013…

…or the recent CVE-2018-4124, when Macs or iPhones froze up after encountering a message containing four compounded Telugu symbols that rendered as a single character:

(For an intriguing overview of complexities of rendering Telugu script, take a look at Microsoft’s document entitled Developing OpenType fonts for Telugu script.)

The February 2018 “Telugu bug” was particularly annoying because a notification containing the dreaded character could cause the main iOS window to crash and restart, and to crash and restart, and so on.

Unsurprisingly, given the ease of copying and pasting the treacherous “crash character” into a message and sending it to your friends (or, perhaps, your soon-to-be-ex-friends), Apple really needed to get a patch out quickly.

And now it has.

What to do?

For your iPhone, you ‘ll be updating to iOS 11.2.6; for your Mac, you need the macOS High Sierra 10.13.3 Supplemental Update.

To make sure you’re current (or to trigger an update if you aren’t), head to Settings → General → Software Update on iOS, and to Apple Menu → About This Mac → Software Update... on your Mac.

Oh, and if you will forgive us a moment of sanctimoniousness: if you were one of those people who sent your (ex-)friends a message containing the Telugu bug because you thought it would be hilarious… please don’t do that sort of thing again.

With cyberfriends like you, who needs cyberenemies?

Follow @NakedSecurity

Follow @duckblog

Article source: http://feedproxy.google.com/~r/nakedsecurity/~3/xqryPr5EWlI/