Are you a student? Your personal data is there for the asking

When parents send their kids (who at that point are legally adults) off to college, they expect not only that they will be educated, but that they will be living in a safe place with a reasonable measure of personal privacy.

Most higher-ed institutions provide at least a measure of that. But when it comes to the privacy of students’ personally identifiable information (PII), not so much. Besides dates of attendance, courses of study, honors and awards and any degrees earned, a lot more is there for the asking – name, home address, school address, email address, telephone number, date and place of birth, possibly even height and weight and some medical records – for just about anybody at a US higher education institution.

This is in spite of, or perhaps because of, the 1974 federal law that sounds like it would protect student PII – it’s titled “The Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act” (FERPA). That law requires “education records” to be kept private, but not “directory information”.

And, says Leah Figueroa, a data analyst who has worked in higher education for 13 years, directory information is being shared without the knowledge or consent of the students – unless they have the savvy to put a “privacy hold” on it, which as a practical reality is about as likely as people reading all the way through a “privacy policy” and “terms of use” statement before clicking “agree” to use an operating system, a social media site or their favorite mobile app.

At one level, this may sound low risk – the kind of information that, as Bret Cohen, an attorney at Hogan Lovells with a focus on student privacy and data collection, put it, “would be typically published in a student directory provided to other students, or in a program handed out at a school athletic event”.

It’s just that the days are long gone when that information was just on paper and pretty much stayed on campus, or was sought mainly by researchers or employers looking to verify a candidate resume. In a digital world, thousands of those records can go anywhere, instantly.

And they do, said Figueroa, who now works at a community college in Texas (that’s as specific as she wants to get). She estimates that the college provides an average of 90,000 student records per year. If the requests come under the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA), “we’re not even allowed to vet them,” she said.

According to FERPA, directory information, “would not generally be considered harmful or an invasion of privacy if disclosed”. But Figueroa said colleges can pretty much decide what to include, which could mean a student photo, student ID and parents’ names, address, and where they were born, in addition to the list above.

She said while many of the requests are legitimate – from researchers or other colleges seeking to recruit students – some are likely coming from predatory loan companies or other kinds of aggressive marketers. A stalker could even find out the dorm address of a student.

That directory information, along with any degrees earned and dates of attendance is enough to, “create fake identities, to dox people, to do just about anything,” she said.

Figueroa presented a talk on the topic in April at Infosec Southwest titled “FERPA: Only Your Grades Are Safe – OSINT in Higher Education,” and more recently in a Skytalk at Defcon in Las Vegas. Paul Roberts, editor-in-chief of the Security Ledger, also featured her in a recent podcast.

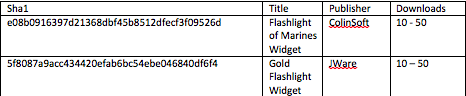

In that talk, she described doing her own small survey of colleges to see what they would turn over. In one case, she said for $50 the institution sent her directory information (emailed and unencrypted) on more than 22,000 students that included the names and addresses of the parents of international students.

Another privacy hole can be medical records, which generally fall under the Health Insurance Privacy and Accountability Act (HIPAA). But Figueroa said a student’s medical records can lose HIPAA protection if anyone but the designated provider requests them – even the student.

Then they suddenly become education records, and they lose all HIPAA protection.

Yes, students do have the right to put a so-called “privacy hold” on their directory information, but Figueroa says most educational institutions aren’t very proactive or consistent about letting them know about it or how to do it.

There’s no standardized way that you have to let students know. Some places it’s on the website, some in catalog, school fact book or some other esoteric place. Some schools let you just sign in with your ID to opt out, some you have to be physically present.

Cohen said the law does require that schools provide notice of the types of information considered “directory,” and the right to opt out. But he added that “there is probably room for privacy-conscious schools to make this information more readily available”.

Figueroa said she sometimes feels like she’s on a one-woman crusade. But she has company. The Electronic Privacy Information Center proposed a Student Privacy Bill of Rights in March 2014 that called for, among other things, making it easier for students to access and amend their records, to limit the collection and retention of records and to forbid using it “to serve generalized or targeted advertisements”.

EPIC also sued the US Department of Education in 2012 over what the group said were “unlawful” changes to privacy provisions in FERPA, but that went nowhere – it was dismissed in September 2013, with the court finding that neither EPIC nor co-plaintiffs had standing.

Still, Cohen said there has been progress. He cited the Data Quality Campaign, which reported that from 2013 through September 2016, “36 states passed 73 student data privacy bills into law. Congress has introduced a number of student privacy legislative proposals, and more than 300 education technology providers have taken the Student Privacy Pledge since it was introduced at the end of 2014.” He added that

… while there is room for FERPA to be modernized, I think that the most impactful way to protect student privacy right now is to better inform students and parents of their rights.

Theresa Payton, CEO of Fortalice and a former White House CIO, agreed.

I would love for students to be able to opt-in/opt-out of having their information shared and fully understand the implications of the state of their personal privacy. I’d also like to see more anonymization of student data for research purposes and trend forecasting.

Figueroa said the bottom line is that the risks from handing out that information to whoever asks is more of a threat than students, or even their parents, realize. “It’s a treasure trove of PII that you can use to do all kinds of things,” she said.

Follow @NakedSecurity

Follow @tarmerding2

Article source: http://feedproxy.google.com/~r/nakedsecurity/~3/FKBR7H__Bl8/

![[Strategic Security Report] How Enterprises Are Attacking the IT Security Problem](https://stewilliams.com/wp-content/plugins/rss-poster/cache/7c01d_Strategic_Security_Report_Thumbnail.jpg)